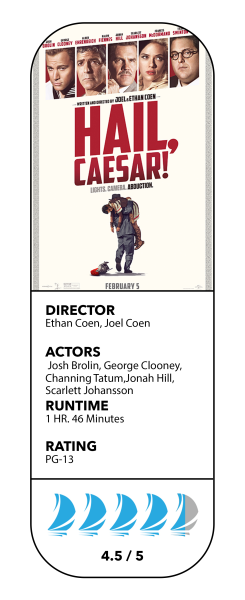

Hail, Caesar is a movie the Coen Brothers were dying to make. Hail, Caesar borrows so many of the Coen Brothers’ favorite elements (Minnesota and the Jewish experience excluded). They like their comedies black, the plotlines multi-layered, and ridiculous with noir elements, the western, and an appreciation of Hollywood’s past. Rather than mocking the saturation and dying creativity of 1950s Hollywood of Barton Fink, we get a first-rate view from an ultimate Hollywood insider. This grand effort to capture the best and worst of Hollywood’s past showcases the abilities of the best directorial pair in the last thirty years.

Josh Brolin is Eddie Mannix, a veteran of the business of the vice behind the glamour of the studio system during the so-called “Golden Age.” Mannix’s daily schedule involves the frenzy, like finding a pregnant actress a temporary husband so her fans think she’s “wholesome,” or changing the image of a star from cheesy-westerns to regal dramas. Mannix tries to protect the talent and pictures his studio owns from the law and twin gossip reporters out to skewer them (both Tilda Swinton). Then a rogue group of Hollywood communists kidnap Baird Whitlock (George Clooney), the star of an epic Quo Vadis lookalike called Hail, Caesar, and off we go.

It’s important not to verge too far off in Coen Brothers worship because Hail, Caesar — a movie about movies— is a difficult film to pull off. The Coen Brothers take their comedies black, but Hail, Caesar has more of a whimsical fare on par with The Ladykillers or The Player, with a glamor of Hollywood’s darker side and its McCarthy-era ideological struggles.

We tend to have a distorted view of past film eras. If you think of the films in the 1940s, you think of highbrow legends like Citizen Kane or Casablanca, not the more prevalent B-movies. Massive studios owned all the means of production and had to consistently churn out a variety of terrible films.

There are several worthwhile vignettes of “movies within the movie.” The scenes don’t exactly mesh with the film as smooth as they could, but for some reason you can’t stop smiling. And who doesn’t want to see Channing Tatum sing in a tight sailor uniform? The Coens succeeded in capturing extinct styles of film like aquatic specials, or “singing cowboy” western comedies.

Which, is important because the flashy ensemble cast of Hail, Caesar never come onto their own—prepare to be disappointed if you thought Scarlett Johansson and Jonah Hill would have more than seven seconds of screen time. They’re pieces in the puzzle the Coens construct, and this is a film where the directors are firmly in control. The dialogue is snappy like Miller’s Crossing, and abound with anecdotes that are common knowledge by few film historians.

There are religious overtones, existential problems and socio-political problems — the typical Coen excursions. Luckily Hail, Caesar is satirical rather than sanctimonious. So what do the Coen’s have to say about Hollywood? There’s a moment which an in-character Whitlock forgets his line on a particular word: faith. It means Hollywood has none, and I think the Coen’s are perfectly fine with that.

—

For more information or news tips or if you see an error in this story or have any compliments or concerns, contact entertainmentnews@unfspinnaker.com.