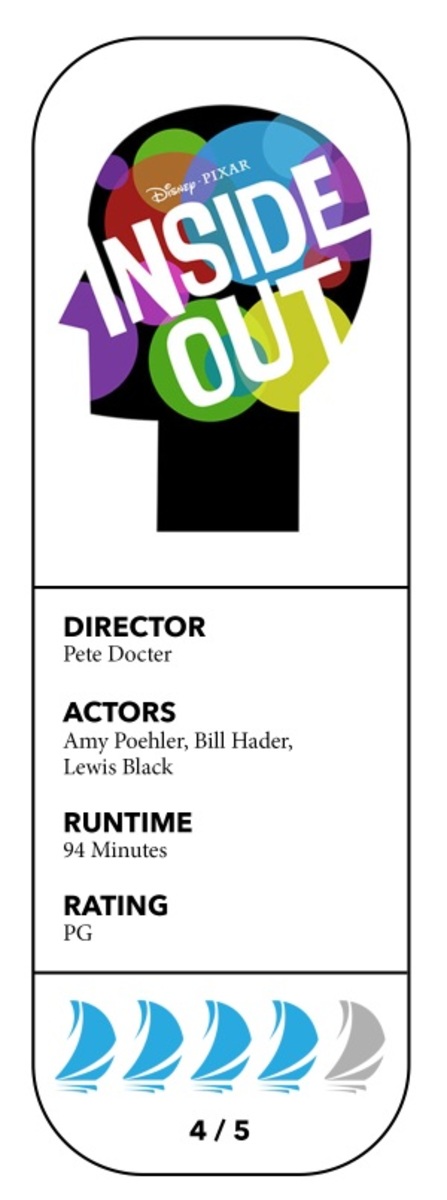

By the end of the 2000s, Pixar had turned into such adept storytellers that they could weave an ambitious, heartbreaking saga of a couple’s life in just the first ten minutes of a movie. That movie was Docter’s last feature, Up, and to follow it up, he decided to go inside the mind. Inside Out proposes that our thoughts and actions are controlled by five emotions: Joy, Sadness, Fear, Anger, and Disgust. Personified, they see the world through our eyes and choose how we respond to it. They also guard over “core memories” that correspond to our personality traits, symbolized in the film as “islands.” For instance, I remember the first time I listened to my favorite song, so there might be a music island in my brain.

The film follows the emotions of Riley, an 11-year-old girl, as she and her family move from Minnesota to San Francisco, a transition they have a hard time adjusting to. To worsen this, a snafu in Riley’s brain HQ leaves Joy (Amy Poehler) and Sadness (Phyllis Smith) stranded with the core memories in the outer areas of the brain, leaving Anger (Lewis Black), Disgust (Mindy Kaling) and Fear (Bill Hader) at the helm. Joy and Sadness must find a way to return to HQ and restore the memories before the others lose control and Riley loses feeling altogether.

This is a very abstract concept, hard to explain in words. Onscreen, however, Pixar manages to get it across very easily, perhaps too easily. Each personified emotion and each marble-like memory sphere gets color-coded. Happy memories are yellow, sad ones blue, and so on. Essentially, it reduces Riley’s experiences down to the whims of her emotions, with each incredibly assured that their choice is the right choice – Joy especially. The mishap that leads to their accidental expulsion comes from Joy’s refusal to let a new, sad core memory join the other five, all happy. But through her time in the woods, Joy learns that although Sadness serves less of a practical function than the other emotions, her input is required to make Riley a fuller person, and that no one can be happy all the time. Once-happy memories are given a bittersweet tinge, for while they cannot be relived, they can be reflected on. Essentially, she learns the value of catharsis and growth.

This is as beautiful a lesson as Pixar has ever imparted, but it doesn’t arrive without troubling implications. To suggest that the more complex emotions one feels – melancholy, nostalgia, even love – are simply the mixed-up secondary colors of our memories is somewhat disdainful. Additionally, as we watch the film and see who’s at the controls, it spells out exactly what emotions are acting on Riley, rather than displaying them. It breaks one of the important rules of visual storytelling, which is that you don’t state your character’s emotions outright. That makes me angry!

Maybe I’m expecting too much, as this is clearly a movie for children. But that’s the problem. Here in North America, animation is still largely regarded not as a separate medium for film, or a tool for artists and directors to use, but a genre synonymous with children’s entertainment. Think about it: would you see the new Dreamworks movie without a kid in tow? This mentality has seen a reversal recently – people seem to get a kick out of Despicable Me’s Minions, for example – but it’s still around, as seen in the lack of genuinely mature animation in American film. Pixar has been resistant to this pidgeonholing for most of their history because their films have always managed to be entertaining for all by presenting mature themes poignantly in a way that kids can recognize. I never really understood the fear of losing an only child that Marlin had in Finding Nemo – I still don’t, thankfully – but I could empathize with him and Nemo, even though I was only eight when I first saw it.

And remarkably, even though I’m being told how Riley is feeling and why she’s doing things, and even though I resent the idea that people can be boiled down to what they think and feel, I still found myself moved. Near the end, Riley’s conflicting decisions put her on a path that threatens to disconnect her from her emotions entirely. This is the film’s worst case scenario, one consistent with symptoms of depression. Ultimately, Inside Out tells us that emotions, no matter how much trouble they give us, are what make us whole, and losing touch with them is a tragedy. Pixar may be trying to tell us what to feel, but it also tells us what we need to know, about ourselves and about how much catching up the rest of the animation industry still has to do.

—

For more information or news tips, or if you see an error in this story or have any compliments or concerns, contact news@unfspinnaker.com.