Updated 8:35 p.m., Dec. 14, 2023: The survivor’s alleged assaulter is not named in the fall 2023 commencement program found on UNF’s website, but it’s unclear when that changed from what the victim was told. UNF did not inform the survivor that he wouldn’t be there. <<Find out more here>>

This article was updated at 7:22 a.m., Dec. 14, 2023, to include a statement from UNF sent after publication.

Content warning: This article discusses and contains descriptions of sexual violence. The National Sexual Assault Hotline can be reached at (800) 656-4673. For more resources, visit here.

Beneath the crisp silver and gray University of North Florida seal, hundreds of graduates will receive their diplomas on Friday. They’ll look out at cheering family and friends, capping off years of accomplishments.

But for one student, the day will be different. As they look over the crowd, they’re worried they’ll see the man they say sexually assaulted them at the start of their college career. A man who will walk across the stage within minutes of them. A man that a university investigation, which concluded in mid-October, confirmed he’d assaulted them.

The victim found out they were set to graduate in the same ceremony as their assaulter months ago and asked the university if he could be prevented from walking. But that request went nowhere for months. The student described being stonewalled until they made a final Hail Mary attempt: calling the president’s office. Less than 48 hours before they were expecting to walk, they received a call from the school addressing some of their concerns.

Now, they question why the university spent all that time on a response, only to change things at the last minute following their persistence as well as over a month of investigation from Spinnaker. One expert says the victim’s story illustrates an ongoing problem at universities when it comes to protecting students from further trauma regarding Title IX investigations.

Education over discipline

Two years ago, H. was sexually assaulted three times within the same night by the same man in their dorm room. They’d moved into the dorms as a freshman earlier that week, with classes starting in a couple of days. They are identified in this article only as H. because of safety concerns.

At the time, they reported the incident to the University Police Department but decided not to pursue criminal charges. Over the years, the school’s Title IX department started, closed and reopened its investigation after H. decided to file a formal complaint in 2022.

Ultimately, the investigation found H.’s alleged assaulter responsible for four Code of Conduct violations, including sexual harassment and sexual assault, according to a written determination from Dean of Students Rachel Winter that H. supplied to Spinnaker.

The university determines Code of Conduct violations; they are not the same as criminal charges, which involve a court of law.

Spinnaker is not naming the alleged assaulter because no criminal charges have been filed. The student didn’t respond to Spinnaker’s multiple requests for comment.

According to her written determination, the dean of students decided an educational response was appropriate. Winter required the student accused of the assault to complete a consent course and reflective essay. He was also placed on disciplinary probation for the remainder of his last semester at UNF.

For the assaulter, his life at UNF didn’t appear to change.

His admission to investigators that he fondled and sexually harassed H., plus the dean of students’ further determination that he sexually assaulted H., appeared to have no impact on his status as a student or a member of UNF’s Greek fraternity and sorority life. Though he was put on disciplinary probation, he would need to break the Code of Conduct again to be considered for suspension or expulsion, according to the written determination.

Pictures posted to his public social media profile show him at fraternity events and parties in the time since the assault.

Tyler Aldinger, the associate director of the UNF Office of Greek and Fraternity Life, denied to confirm whether H.’s assaulter is still an active member of his fraternity, writing “I must inform you that the University will not discuss any specific student information.” However, his public social media and LinkedIn accounts indicate that he is, as of publication.

‘Don’t stir the pot’

The night of the assault in 2021 was the first time the pair, who H. said had been dating online for about two months, met face-to-face. H. didn’t want him to drive back to his dorm in the middle of the night, so he slept over.

H. told investigators the man woke them up in the middle of the night three times, attempted to have sex, fondled their breasts, fingered their vagina and engaged in other sex acts without their consent, according to a recounting of the investigation included in Winter’s written determination.

He woke them up “because he was horny and he wanted sex from me […] If I spoke up, I was worried he would hurt me,” H. told investigators.

Just starting their freshman year, H.’s time at UNF was ruined before it began. Panic attacks became their norm, brought on by the fear of running into him. They struggled with their mental health and said they failed at least one class.

One of their psychology classes assigned work that discussed sexual disorders without any warning, H. told university investigators. They had to do alternative assignments to avoid being emotionally triggered—which was arranged by UNF’s Victim Advocate services.

The school’s investigation took months to complete. During that period, survivors aren’t meant to be alone. That’s where the Victim Advocacy Program at UNF is supposed to come in: providing judgment-free and confidential services to UNF students, faculty and staff dealing with sexual misconduct of any kind, according to their website.

The purpose of a victim advocate is to present victims with options and connect them with people who can grant them support. It’s also their job to provide emotional support and ensure that student’s rights are protected, said Brianne Vallenari-Frieder, a former UNF victim advocate with 16 years of experience in the field. Vallenari-Frieder was also the original victim advocate assisting H. before leaving the position to pursue further education.

But after Vallenari-Frieder left, H. sought out her replacement—UNF’s current Victim Advocate Maurisha Bishop-Salmon—for additional accommodations and support. Instead, they said they were not provided clear guidance regarding who to talk to and a lack of action when they requested their assaulter not walk in their graduation ceremony.

Advocates are expected to work with student victims to effectively return their autonomy by presenting all their options and following them down whatever path they choose, explained Vallenari-Frieder, who declined to comment on specifics of H.’s case, citing confidentiality laws. But H. said that didn’t happen here.

When H. asked Bishop-Salmon in October for help facilitating an accommodation so they wouldn’t have to see the man who assaulted them at their graduation ceremony, H. told Spinnaker Bishop-Salmon discouraged them from pursuing it.

“She said that there was no way that he would be prevented from walking at graduation and that it’s best for me not to stir the pot and not to get my hopes up,” H. told Spinnaker.

Last week, Spinnaker presented UNF with a waiver from H., granting the university express permission to discuss their case, but school personnel refused to comment.

Instead, the university asked for questions to be sent over email. Spinnaker sent UNF detailed questions on Monday asking what transpired during and since the meeting where H. wanted to pursue supportive measures, but a university spokesperson didn’t respond until after publication at 7 a.m. on Thursday. Amanda Ennis, UNF’s media relations manager, said the university declined to comment on Spinnaker’s questions because the university “won’t discuss specific student information.” Ennis also included a statement about the role of the victim advocate and a statement from the Victim Advocacy Program:

“[Victim Advocate Maurisha Bishop-Salmon] you are referencing has a long and distinguished background in advocacy at UNF and with the City of Jacksonville and just started in this current position at UNF in September. She is highly trained in compassionate victim support and de-escalation methods and equipped with tools and resources to aid victims through the recovery process.”

H.’s conversation with Bishop-Salmon happened over a month ago, and they say they haven’t heard a word back about whether that request was ever presented to anyone beyond the victim advocate.

This isn’t unheard of, one expert said. Andrew Davis, a student engagement organizer with Know Your IX and a Brown University graduate student, called H.’s interaction “shocking but not surprising” and “really disappointing.” Know Your IX is a survivor- and youth-led project based in the U.S. aiming to empower students to end sexual and dating violence in their schools.

H. said while they expected the Victim Advocate’s office to fight for them, instead Bishop-Salmon suggested the reflective essay should have been enough closure.

Davis said there were other things UNF could have—and should have—done for H. In this case. Bishop-Salmon should have been “leading the charge for any of these accommodations,” Davis told Spinnaker.

“Schools can do a lot more than they’re legally required—that’s the floor,” he said. “There’s plenty of states that have amazing state-based legislation on campus-based sexual violence that go even further than Title IX and provide all these extra supportive measures and protections.”

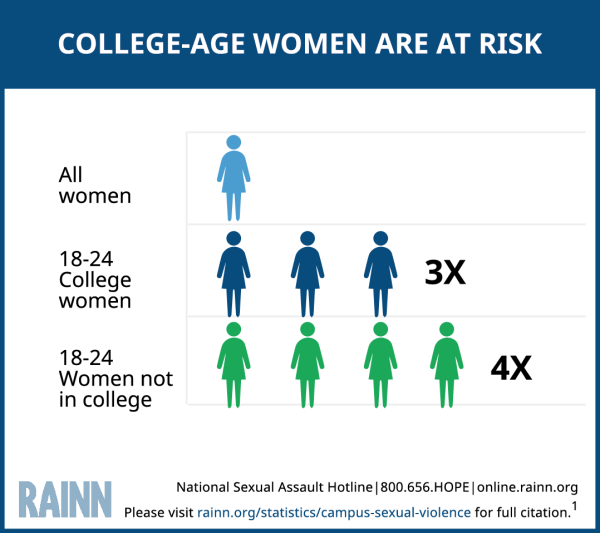

Sexual assault is pervasive on college campuses: Women ages 18-24 who are college students are 3 times more likely than women in general to experience sexual violence, according to the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network (RAINN). About 23% of transgender, genderqueer or nonconforming college students have been sexually assaulted, according to RAINN. H. identifies as nonbinary.

In a recent report, the U.S. Government Accountability Office said higher education institutes can better support sexual assault survivors by providing individualized safety plans. Some examples included in the report, based on interviews with colleges and organizations that work with sexual assault survivors, included offering students escorts around campus, changing their housing and tailoring mental health services for their needs.

A last-second response

During an interview about the purpose and process of Title IX investigations, the dean of students told Spinnaker that if a student’s actions create a safety concern for campus, they evaluate the safety of campus against the student’s individual actions. That evaluation determines what the response looks like, she said.

But H. questions the effectiveness of the university’s disciplinary response. They say Winter’s decision to counter an assault with education for the assaulter didn’t protect them or the campus. Davis with Know Your IX agrees: “As the survivor in this case, they are the best positioned to know what their campus needs in terms of protecting survivors and students from harm.”

H. told Spinnaker that they feel even more unsafe on campus, knowing that someone could be found responsible for sexual assault Code of Conduct violations and still be allowed on campus.

“It also makes me feel a bit invisible,” H. said. “Like my fighting was useless, that I put in all this work to try to get even the tiniest bit of justice.”

In a last-ditch effort, H. called UNF President Moez Limayem’s office earlier this week and said they were told they’d get an email about potential supportive measures. They didn’t hear back until a phone call from the school’s Enrollment Services around 6 p.m. on Wednesday.

Their assaulter will still walk in their ceremony, H. told Spinnaker, but H. was granted other accommodations. Spinnaker is not specifying the new accommodations to protect H.’s identity.

Still, with less than 36 hours until they’re set to walk across the stage, H. says they don’t understand why they had to go to such lengths to feel acknowledged and do what they believe was the victim advocate’s job.

“It’s crazy that I had to call the President’s Office to get this, and that it could be fixed this quickly,” they said.

Now, H. is excited to close this chapter and receive their diploma. They’re looking forward to turning their tassel, not looking over their shoulder.

___

For more information or news tips, or if you see an error in this story or have any compliments or concerns, contact editor@unfspinnaker.com.

dosachy | Dec 14, 2023 at 6:20 pm

Thank you, Carter and the Spinnaker, for investigating and reporting on these issues. “Missoula” by Jon Krakauer should be required reading for all college students to understand the complexities of this epidemic. The more people that know, the better. Authorities need to be held accountable when it comes to their inaction and ineptitude.

Dr. Ursula Scott | Dec 14, 2023 at 2:41 pm

This is quite unfortunate and occurs far too often on campuses across the country.