Photo source: http://bit.ly/LV9Cby

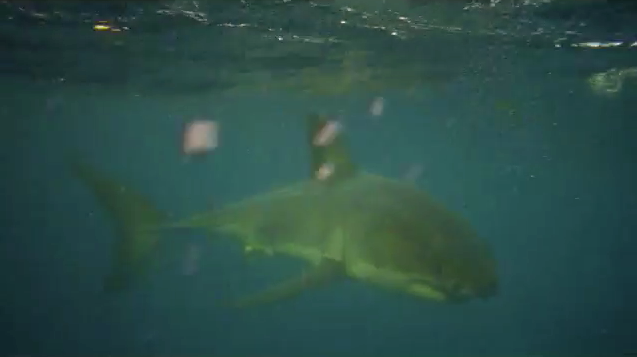

Shark research group OCEARCH tracked a great white shark just outside the Jacksonville Beach surf zone on Jan. 8.

Mary Lee, 16 ft long and 3456 lbs heavy, is one of many white sharks tagged off the shore of Massachusetts and tracked by Dr. Greg Skomal with OCEARCH.

Genie, a 14 ft, 2292 lb great white also visited the Jacksonville area. Genie stays further offshore while, according to Dr. Jim Gelsleichter, UNF assistant professor of biology, Mary Lee stays about 15 to 20 miles offshore the majority of the time.

Over the past decade, the number of white sharks off Massachusetts has increased, due to a healthy seal population. Along with this population increase, there has been an increase in shark sightings and, consequently, beach closures.

For the most part, the white sharks are only feeding opportunistically on the carcasses of right whales.

The city of Jacksonville Beach did not close the beach while Mary Lee was just outside the surf zone.

“There are always sharks in the water, this one caused a scare because of its size and species,” said Lieutenant Taylor Anderson, a 10-year veteran with Jacksonville Beach Ocean Rescue. “If there is a shark close to shore, we clear the area of bathers.”

“There is a fine line between protecting people and causing a panic. We do what’s in people’s best interest,” said Anderson.

Causing a panic may not be something Ocean Rescue has to worry about. Shark reports haven’t been enough to keep Jacksonville surfers away.

“I think it’s funny that people worry about one shark and don’t realize there are others without trackers,” said Jarrod Forsythe, a public relations junior. “You can’t let one known shark kick you out of the water.”

“I surf all the time and I haven’t seen [the shark]. Only thing that’s scary is that we wear black wet suits that make us look like seals and all the more appealing,” said Michael Wilke, a communications sophomore.

Photo source: http://bit.ly/LV9Cby

White sharks have been known to migrate south during the winter for some time, but the tracking with real time tags has revealed interesting patterns.

“Not only are they here, but they are probably staying here longer than we thought. We have known that they move down here for a while. It was only a few years ago that we started to get tag information,” said Dr. Gelsleichter.

The real time tags used by OCEARCH are attached to the shark’s dorsal fin and submit a signal every time the dorsal fin breaks water, enabling for better tracking than with previously used pop off tags. The pop off tags would stay on the shark for a period of time before popping off and floating to the surface. Only after the tags popped off and reached the surface did they submitted a signal giving information about where they had been.

In addition to sharks, Lt. Anderson pointed out that there are other dangerous and more frequent hazards associated with the beach such as jellyfish, riptides, and sun exposure. A riptide is a narrow channel of water that flows back into the ocean and can sweep swimmers out to sea.

“With UNF having many students from other areas of the country, we encourage them to stay near a lifeguard and ask about beach safety,” said Anderson.

“We are not sure what influences their movement patterns but it is probably driven by food and reproductive behaviors. One belief is that they’re following the right whales while calving, but there is no indication that they are targeting them,” Dr. Gelsleichter said.

Dr. Gelsleichter has started to develop a public database that monitors white sharks in the area. He hopes to be able to work with OCEARCH to use acoustic receivers to listen to the sharks as well as tag them.

Email Kathleen Godfrey at reporter12@unfpsinnaker.com