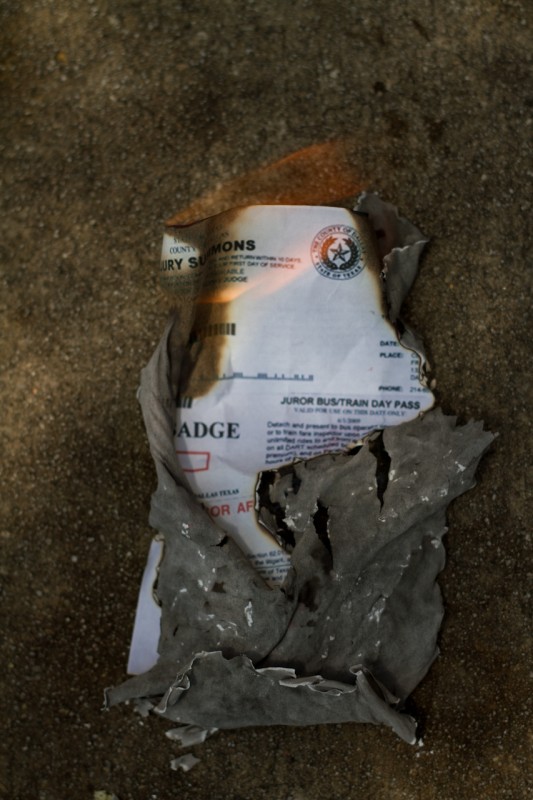

Photo by Randy Rataj

The man adjacent to me pleaded to the judge, in broken English, that he doesn’t speak or understand English. I overheard him fifteen minutes earlier, speaking perfect English to another Hispanic man in the lobby. That other Hispanic man shortly followed with the same plea. They were almost immediately dismissed from the jury selection process.

Few people are excited by jury duty — and for good reason. It’s a tedious ordeal that takes people away from their daily routines to instead sit in a courtroom for hours on end. Upon seeing a juror summons letter in the mail, many emotions come to mind, but joy is not one of them.

On their assigned summons date, the summoned person reports to the courthouse and proceeds to a large room where they sign in. From my experience, this room is hellish. It smells of old carpeting and is filled with hundreds of other people who are equally unhappy to be there, The PBS or Animal Planet program being played on the room’s three TVs doesn’t make anything better. After signing in, you get a juror badge and wait for your name to be called over a PA system.

While waiting, you can either read a book you have brought, marvel at the banality of the TV program being played or people-watch and try to pick out who is the least enthusiastic about being there.

On my day of jury service, my name was called after an hour and a half of stagnating in that room. I was selected with 40 other potential jurors to undergo the juror selection process for a criminal case.

Once we were all seated in the courtroom, the judge introduced himself. Aesthetically speaking, he was the epitome of normalcy – brown, short hair with few streaks of white and grey with subtle facial wrinkles. He was in his mid-forties and was very articulate with a slight Southern twang in his speech.

The juror selection process took about two and a half hours of being collectively and individually asked questions by the judge, the prosecution and the defense. They assessed who was able to be a fair and impartial juror out of the 40 in the room. Seven people were eventually selected.

So I sat in a courtroom with 39 of my peers on some of the most uncomfortable pews imaginable. Within the first 15 minutes of selection, seven people claimed they were incapable of understanding English, and four people said they were too openly racist to be impartial in a criminal trial that dealt with a Haitian male.

Yes, that’s right. Some people were either painfully honest with who they were, or, more likely, so eager to get out of jury duty that they were willing to label themselves as racist. I find this embarrassing. I would have rather told the judge that I didn’t speak English in perfect English than claim to be so racist that I couldn’t be fair in judging someone with a different skin color.

On another level, the case at hand was abnormal. It involved a man being accused of committing lewd and lascivious behavior (through public masturbation) in the presence of a minor under the age of 16 years old. Upon hearing this, many potential jurors felt uncomfortable; there went another 10 people, leaving my odds of being selected greater and greater with each passing sentence about masturbation.

Oddly enough, the more I heard about this case the more interesting I found it. It was peculiar. This isn’t to say that I was eager to be selected, but when the moment came between deciding to give the process of jury selection a fair chance, or lying about being uncomfortable and being discharged — I kept silent to give the system a fair chance.

After a lunch break, I was officially chosen to serve on the trial.

Basing this off rough estimates, the mean age of the jury chosen was about 40 and the range was 21-60. I was the young buck, and stuck out like a giraffe at an elephant convention.

Before one serves on a trial, the judge explains several concepts about how our judicial system works.

The first concept is the presumption of innocence, which means the defendant, in any case, must be presumed innocent until proven guilty.

The second is that the state prosecutors had to meet the state’s burden of proof, meaning that it is the prosecution’s responsibility to provide enough evidence for the defendant to be deemed guilty beyond a reasonable doubt.

The third was the ability to be impartial, which should be self-explanatory.

And the fourth was the defendant’s right to remain silent, meaning that we can not pass judgment of guilt or innocence based on the defendant choosing to remain silent throughout the trial, which he did.

The trial proceeded for the next two days. The jury was barraged with photographic evidence, a wide variety of testimonial evidence and opening and closing arguments by both the defense and the state attorneys.

At the end of the trial, the jury was sent into a back room to conference about the trial and to come up with a unanimous decision of guilty or not guilty. After about half an hour of deliberation we did find the defendant guilty.

Walking out of the courtroom was sweet relief. The word “liberation” had new definition, but it wasn’t the only thought present. Oddly enough, I walked away from that courthouse feeling good about what went on those past couple of days. I did my civic duty that was created by this country’s brilliant forefathers in an attempt to create a fair and just legal system. If I had been the defendant, I would want my case to be heard by a panel of impartial peers. This isn’t saying that the system is 100 percent correct or foolproof, but it is saying that if a time comes when you must depend upon the fairness of the legal system — whether that means being on trial yourself, being a victim of a crime or having a loved one involved with a case — there’s a good chance that fairness will prevail.

And for those three days, I can admittedly say that I was happy to be a cog in a system that served and continues to serve justice.

Email Carl Rosen at opinions@unfspinnaker.com