Moving away from home doesn’t get any more drastic than in Studio Ghibli’s “The Tale of Princess Kaguya.” The film, directed and co-written by Isao Takahata, reverses the Hayao Miyazaki canon of transporting humans to the supernatural world by instead bringing an alien girl to Earth. The protagonist, Princess, is harvested from a glowing bamboo stalk chopped down by the curious old bamboo cutter. Believing this tiny doll-like princess to be heaven-sent, the bamboo cutter carries the found being home to his wife. The childless old couple raises the girl they call Princess in the countryside and with the graces of the glowing bamboo stalk, are able to eventually establish a noble future for her in the capital. Because of her undeniable radiant beauty, Princess is given the name “Kaguya,” meaning radiant night. Kaguya and those around her soon realize the truth of her origins.

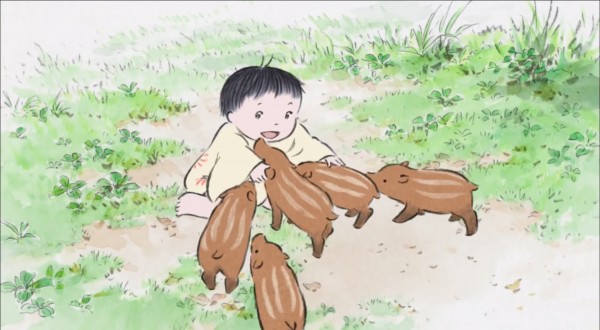

The beautifully hand drawn animation stays true to the 10th century folk tale “The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter.” Though the film follows the tale’s chronology, writers Riko Sakaguchi and Takahata add more characters in the plot and more dimension to Kaguya’s character. The film’s attention to the protagonist’s growth as she learns to laugh and live by the land with her friends highlights her humanity—an aspect that tends to get lost in the glitz and glitter of princess stories. Kaguya grows up in a humble setting and wishes nothing more than to be with the “birds, bugs, bees, grass, flowers, and trees.”

The film interpretation also captures the pure wisdom of a child as Kaguya delivers koan-like requests to her suitors. Instead of accepting poetic proposals she asks for something concrete. If compared to the begging bowl of Buddha, she asks to see the actual bowl of Buddha. This is not done to test her power through impossible requests, but rather to give Kaguya proof that she is not just a wonder. She wants to be perceived as a real person, a human being.

However, overall, the film adaptation of “The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter” is a lengthy tale to follow, detailed with overwhelming ideas ranging from celestial sprites to bodhisattva allusions. What makes the film suffer in comparison to Takahata’s other works (most notably, “Grave of the Fireflies”), is the story being simultaneously too realistic and too unrealistic. Sakaguchi and Takahata’s modern interpretation created relatable characters but also made Kaguya’s situation more foreign to the audience. It is especially difficult to be emotionally invested in characters that overtly state their emotions. Kaguya’s emotional shifts feel unwarranted when her experiences and actions don’t lead up to her sudden mood shifts. That may be a nod to how adolescents act, but nonetheless, it kept me detached as a viewer. The writers could’ve also stepped out of the original tale’s realm and made Kaguya’s alien origins more apparent with hints here and there. Just like the folktale, we learn Kaguya is of the moon way too late in the game.

For those familiar with Isao Takahata’s work and Studio Ghibli, “The Tale of Kaguya” may not fall in as a favorite plot-wise. The animation with its expressive lines and understated watercolor palette is something to admire, for sure, making it possibly one of Ghibli’s best pictures. The dream sequences, specifically, showcase how dynamic the film is. But unlike other Ghibli films, “The Tale of Kaguya” isn’t as captivating. While reversing the Miyazaki canon certainly redefines what is magical by emphasizing the wonders of being alive on Earth, and Kaguya’s experience moving from Moon to the countryside to the capital hammers home the feeling of uprootedness, the film still falls short. “The Tale of Kaguya” is a fresh take on a folktale, but it is not as strong as titles like “Spirited Away” and “Princess Mononoke,” which both also stem from Japanese folklore.

I give “The Tale of Princess Kaguya” 3 out of 5 Spinnakers because of my expectations of Studio Ghibli. I do highly recommend the film for its picture and sincerity in plot. The modern interpretation of the folktale embraces the grandness of humanity with its cycle of love and pain—a refreshing theme from a studio so immersed in elaborate fantasy. If possible, see the film in Japanese with English subtitles. The dubbed version personally drew me away from the story with its off-putting translations of nursery rhymes and awkward speech. Otherwise, “The Tale of Princess Kaguya” is an animated treasure, despite its weaknesses in plot.

Email Shannon Pulusan at copy@unfspinnaker.com