Thanks to a bunch of word nerds in the 4th century, we’ve all been shitting ourselves over nothing. Turns out, there is no hell. At least not in Christianity.

Scholars in the Middle Ages incorrectly translated the Hebrew word Sheol and Greek words Hades and Gehenna as Hell. The Bible’s translation from Hebrew and Aramaic to Greek, then Latin, and finally English has added elements of pagan mythology to the afterlife — something Jesus couldn’t have intended.

There is no basis for Christians to believe in hell. Jesus didn’t teach about the

Christian Hell. In Jesus’ culture there was no eternal damnation — the concept was tacked on later.

In the Greek Bible, Hades served as a poor translation for Sheol: the Hebrew word for death, which also means “pit” or “abyss.” Hades is the Greek underworld and all dead generally go there permanently. It was underground and there was also a punitive wing of Hades called Tartarus. The closest thing Greek Mythology has to heaven — Elysium — is in Hades. Hades eventually became hell in the English translation. It has figured into Christian damnation’s permanence and the notion of a subterranean hell. Tartarus specifically influenced Hell as a place of punishment.

Gehenna also appears in the Greek Bible; it is the Greek name for the valley in the Old Testament where heretical Jews burned their children in sacrifice to pagan gods. Old Testament Prophets said God will burn his ever-straying chosen people in Gehenna.

Throughout the Bible, Gehenna is also figured as a place where souls burn in tribulation for, at most, 12 months before going to God. When Jesus refers to hell, he is often referring to Gehenna, not anything permanent or physically disciplinary like Tartarus. Jewish custom and culture inspired Christian conceptions of hell fire and brimstone. Hades was actually a cold place.

Judaism’s fiery, purgatorial Gehenna and the eternal punishment of Tartarus influenced a picture of the permanent, punitive Christian hell in biblical translations up to and including the Latin Vulgate — the Catholic Canon which dominated christianity for a millennium.

The Vulgate translates death and the afterlife as Infurnus and later English versions call it hell. Both words have roots in Proto-Germanic, a 2.5 thousand year old precursor to English and 12 other European languages. They had pagan associations when the church began using employing them in translation.

By mentioning hell, Jesus characterizes the afterlife using a word that didn’t exist at the time he supposedly spoke it– its roots were just beginning to form in distant Northern Europe.

The Holy Roman Empire had an easier time converting barbarous Germanic tribes because hell was familiar to the tribes’ associations with the Nordic goddess of death, Hel, and the afterlife: The House of Hel.

Even the devil’s supposed residence in hell echoes Hades’ and Hel’s.

After inventing hell, the Church integrated the concept into its dogma, and it became a means with which to gain power. Hell was a metaphysical boogeyman used to scare believers into submission to the Church. Be baptized — and thus initiated — or be damned.

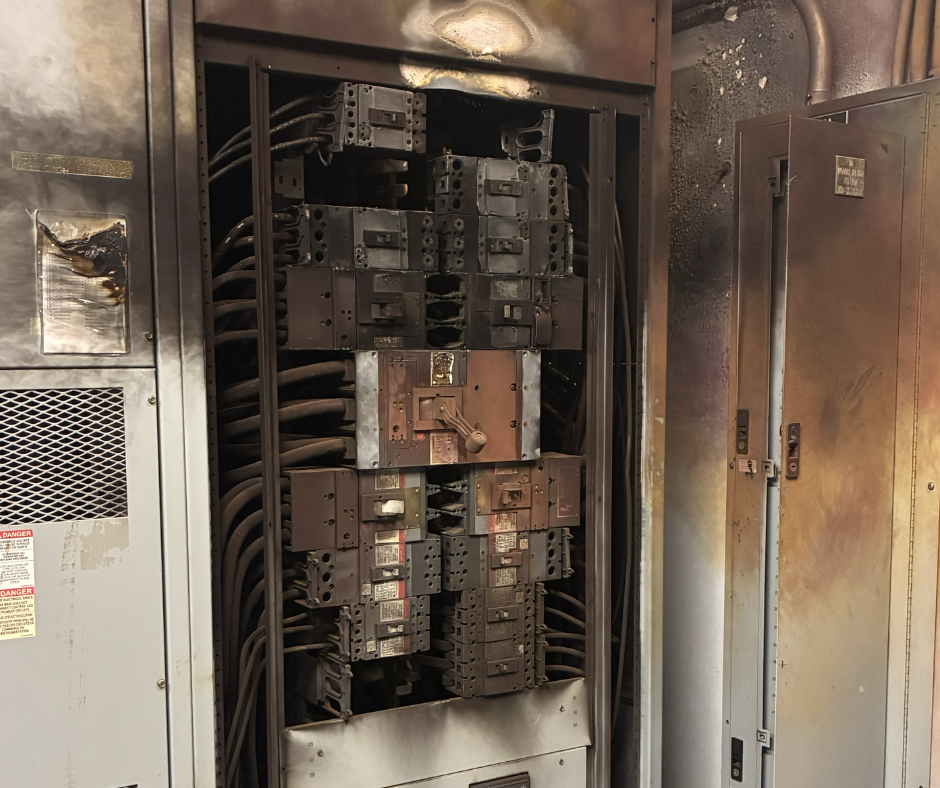

By the 14th and 15th centuries, the pious were paying the Church to stay out of hell by way of indulgences. The Church used the money for infrastructure, education and benevolent (read: missionary) acts — all these institutions allowed the Church to continually reassert and reinforce itself. Oh yeah, and a few clerics were skimming off the top, too.

If hell doesn’t really exist for Christians, as argued for above, contemporary Christianity needn’t be indicted. Hell was institutionalized and taken for granted long ago, but at this point, it is equally outmoded and unstable. Throw some gas on it. I’m sure Christians will find something to do with the ashes once hell’s all burned up.