It’s impossible to overlook Michael Aurbach’s work. Stepping inside the UNF Gallery, viewers are met with two huge metal sculptures. On the piece closer to the door, black urinals contrast with the shiny metal. On the other, handcuffs hang from numbered red cushioned thrones. Lining the walls are pictures of many of Aurbach’s other works, many of which he has had to destroy due to a lack of storage space.

It’s impossible to overlook Michael Aurbach’s work. Stepping inside the UNF Gallery, viewers are met with two huge metal sculptures. On the piece closer to the door, black urinals contrast with the shiny metal. On the other, handcuffs hang from numbered red cushioned thrones. Lining the walls are pictures of many of Aurbach’s other works, many of which he has had to destroy due to a lack of storage space.

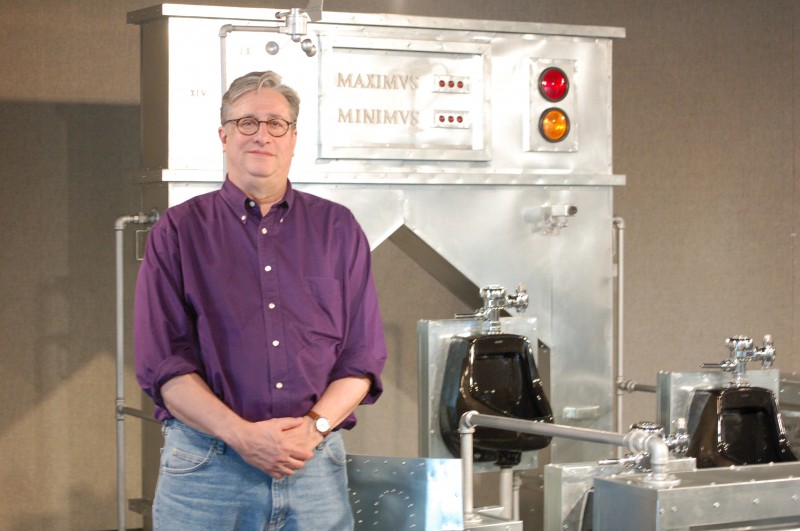

Through his work, Aurbach offers commentary on academia, mortality and social issues. Aurbach has received many grants and awards and displayed his work in over 70 solo exhibitions since 1986. He also teaches sculpture and drawing at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee.

Aurbach recently brought some of his work to Jacksonville, where it will be displayed at the UNF Gallery at MOCA as well as in a companion exhibition on campus at the UNF Gallery of Art from March 5 until April 28. The Spinnaker Spoke with Aurbach March 5 before a luncheon event at UNF.

Spinnaker: What are some of your inspirations for your work?

Michael Aurbach: It’s basically just anything that gets me mad and anything that is irritating me is going to be a good place to start. I’m sort of reactionary.

S: Tell me a little bit about your creative process of making the pieces.

photo by Dargan Thompson

MA: I usually think about a piece at least a year in advance, because the cost associated with producing the works is so high that I can’t just work spontaneously and jump into it. I may get the thought of producing a piece in a hurry or on the spot, but it will be at least a year to a year and a half before I ever produce it because if I don’t have a clear idea of what I’m doing I’ll blow a lot of money in a hurry. So that’s part of the process and then the next part is doing some homework because, you know, once you’ve been to college and you’re an academically trained artist you can’t be naive anymore, you give up that option. So I research the heck out of what I’m doing. And the other thing is, by having such a long period of time to work on it, I can throw out ideas, add something, you know, if I worked in a hurry I’d be overlooking a lot of stuff. So, it’s a problem working slow, but in the end it works out ok.

S: And what about the actual creation of the pieces?

MA: Well, it depends on the piece … They typically take me a year, although a couple of the pieces on the wall here (gestures to the pictures lining the gallery) like The Institution, that took almost three years on that one, and then The Confessional, on the far side there, took almost two years. Some I work very slow, but it’s so costly that I run out of money working on the piece, so until my next paycheck comes in I can’t proceed.

S: I read that you haven’t aligned yourself with any galleries, that you’re independent, so how does that work?

MA: Right. I got a major New York gallery right before I got tenure. That was sort of to make sure I got over the hump of tenure, but I really don’t want to deal with a commercial gallery. They’re fine for some people, I don’t want to begrudge that, but to me they’re not a measure of artistic excellence, it’s just a retail store. My challenge would be if I want to have a commercial gallery it’s going to have to be a major one because the costs I’ve put in need to be recouped. But to do that — to show in New York and live in Nashville is almost impossible. The other thing is, because I wanted to stay in academia, I had to do lots of shows and the only way to do lots of shows is for me to have control of all the work. If I sold the stuff, I’d lose control. So, that was a conscious decision.

S: So how have you survived in the art world without that?

MA: Well, I’m lucky I have a salary that I can depend on. So I’m able to save. In fact, in the end I’m near retiring now, I sort of figured that I’ve probably come out, maybe financially ahead in the end by saving my money through a salary than I would have trying to make sales.

S: What drew you to the medium of sculpture as opposed to other forms of art?

MA: Well in college I was really more painting and drawing, but what happened was I got a job at the woodshop at school and the guy spent a lot of time with me who ran the shop. And I got to the point where, not to put this in the fantasy realm, but if I can fabricate the thing I’m thinking about, why draw it? Why not have the real thing? So that made the leap for me, even though I love the sort of intellectual challenges that come with the two dimensional versions. But I don’t think these things would even make sense in terms of drawing.

S: How do you think the medium of sculpture impacts viewers differently than other mediums?

MA: Well it gets in the way. And because I’m dealing with human subject matter, it works best in a human scale. I don’t think you could have the same impact with a drawing even if it was well done. I’ve never drawn so big, on the same scale like this. I just think sculpture has more of a sort of instant sort of what we used to call keen aesthetic. There’s a sort of a physicality to it.

S: What do you hope viewers take away from seeing your work?

MA: Well I hope the viewers don’t take my art. At least let me start with that because I have vandalism in most of the shows I’m in. But I’m not sure … when I did all those pieces about death that you see on the wall there, I used to think I could sort of control what the viewer would take away. And you can’t, not with death, because everybody comes to the table with different experiences. I hope they walk away with a chuckle, at least — that people in positions of power are often silly and foolish and we all play the game with them. I don’t understand that. I’m at an institution where there’s regular changes in the administration and every time there’s a change more faculty show up at the door and start sucking up to people in power. It just amazes me. I mean, what family teaches their kids to suck up to anybody? Certainly not my family. I’m just amused by it. So, I hope they take away a sense of commonality, that we’re all being led by a bunch of idiots.

S: Is that what you think of when you’re creating pieces?

MA: Well, no. In these cases these are really — I can’t name names, but they’re often inspired by very specific people and very specific conversations. But I try to take them from the specific and throw them into the general. I sort of think all art really has been made by the time of the Romans. I can’t think of any new eternal truths that artists have brought up since then, and if you think about the Greek and the Roman myths and biblical stories, it’s all there. It’s all been done. I mean technology’s one thing, but even if you’ve got high technology you still have to deal with human relationships, relationship to nature, relationship to a deity if there is such a thing. Maybe there’s a couple dozen themes, that’s about it. So I think I’m smart enough to realize don’t worry about doing something new or something fresh, you know, just do something honest.

S: What advice do you have for art students who are just starting out?

MA: Well, first of all, there’s no faking your way through it. I mean, you have to put in the time. Discipline is pretty important. And I think taking as much art history as you can to become aware as quickly as possible that you’re not doing anything new. Get over that hump. Because I think what’s going on in a lot of schools now they teach a thing called critical theory, which is another thing I make fun of with my artwork. And they’re introducing it too early, so the students are getting into a whole realm of psychobabble and it all becomes self referential, and I’m not sure that’s a healthy way to study art. And art gets easier, it should, the more experiences you have. When you’re 18 years old, 19 years old, you do have life experience, some of it can be dramatic, but people are still searching. So just be open and receptive and just pay your dues and put in your time.

S: Has it gotten easier for you?

MA: Well it’s easier in terms of subject matter. I’m willing to take on just about anything now. The hard thing now is sculptors like me who work large, we have sort of a shelf life. I can’t lift and move things like I used to. So I have to design with my aging in mind. And also the costs — I don’t want to bankrupt myself before retirement. So, I’ve just got to watch a little bit, but I’m still pretty open to doing anything I want.

Email Dargan Thompson at features@unfspinnaker.com