After yet another weekend of violence that left both a popular game bar and a high school football game shot up, Jacksonville once again becomes the site of national tragedy. National media, focusing their attention on the mass shooting at the bar, has swooped into the area for what is likely the next site for the ever-continuing national debate on gun violence and mental health.

The Jacksonville Landing shortly after the shooting on Aug. 26.

These are important conversations to have considering this sort of violence seems to be recurring all over the nation, and they are conversations that the Jacksonville community has already been engaged in due to the sheer amount of violence that happens in this city.

I don’t want to talk about those conversations though, because the relative closeness of last weekend’s violence has left me, and I assume much of the UNF and Jacksonville community, struggling to process what happened. The recent violence has, in a way, enlightened me into the realization that I don’t know anything about how to respond, process, or cope with a tragedy this close.

These two shootings both involved young people and students. The Raines shooting left a recent high school graduate dead, two high schoolers injured, and a sixteen year old behind bars. The Landing shooting occurred in a bar frequented by UNF students and the gaming community, the victims and the perpetrator being young men.

Both of these environments are frightening in particular because they are so close to the things many students experience regularly. We’ve all attended high school, and many UNF students are gamers, evidenced by the vibrant gaming scene that exists on campus, or at least frequent bars in the downtown area.

The bar where the violence occurred was always on the table when I’d go out for a drink. Close friends had recommended the place to me as a fun environment, and one of them had won a tournament there previously. While I never ended up going there, I have been to the Landing, and the fact that I could have gone, or that I could have been there when it happened keeps crossing my mind. The shooting happened here.

There’s a sense that tragedies always happen elsewhere, in some place we’ve never seen or been. The violence is always overseas or in some other county or country, until its here in the places I could have been.

These feelings of fear that I could have been a victim are mostly unfounded; I already admitted I’ve never been to the bar, or Raines for that matter, but that sense of closeness causes this fear that threatens the relative peace I’ve known. What once only happened elsewhere now could happen anywhere.

While I could be ruminating on why the perpetrators did what they did, I find myself instead thinking more and more about how we can cope with this fear that it can happen anywhere. Confiding my anxieties in a friend, he told me that perhaps we need to rethink the way we relate to others.

My anxiety about the relative closeness of the shooting is always mixed with the relative foreignness of both the victim and the perpetrator. I, and others, jump to concerns about our own safety or what we’d do, rather than the thought that the next victim or perpetrator could be right beside us.

Especially in regards to the Raines shooting, young men born into poverty, violence, and trauma find communal acceptance in gangs because of a societal failure to provide any alternatives. Perhaps, with a radical rethinking of our social obligations to one another, there could be hope for some change. Instead of more thoughts and prayers after the tragedy has occurred, we can spend our energy providing support and care for one another.

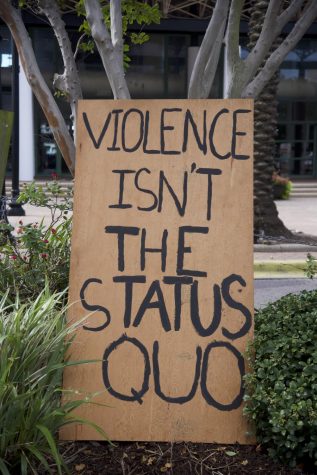

One of many anti-gun signs posted outside The Landing.

Our obligation as a society should be to provide the material and emotional support that can stop young men from being drawn down the path of violence that poverty and despair lead to. The anxiety I feel after these tragedies is not only that fear it could happen to me, but that, in some way perhaps, I could have done something to stop the violence.

I hate to see the city that has always been my home bleeding yet again. Jacksonville can be a cruel and violent place, but that doesn’t mar the beautiful, unique, and diverse community that exists in my city. I hate to see my city bleed because I love its people, and the process of healing begins with sharing that love.

—

For more information or news tips, or if you see an error in this story or have any compliments or concerns, contact editor@unfspinnaker.com.