The second floor of the Museum of Contemporary Art Jacksonville (MOCA) features Shervone Neckles’ Bless This House, a hospitable collection of pieces that explore welcoming themes of family, home, and identity. Through silkscreen, embroidery, and mixed media, Neckles dives into a conversation on the meaning of home.

The title of the collection, “Bless This House,” is named after her great great grandmother’s favorite song of the same name.

The song means a lot to Shervone (specifically the Mahalia Jackson 1956 rendition) because of the song’s lyrics. She says that when you read the words to the songs and listen to the way Mahalia Jackson sings them, you realize that it’s not just about the house.

“It’s about the community surrounding the house, and that it’s not only just blessing the home because we carry home within us – like home is us. So it’s like ‘bless us too,’” Neckles explained in an interview with Spinnaker.

That sentiment is translated through the exhibition’s use of curtains at the entrance of her gallery.

“It’s kind of like you’re entering this space, and I’m saying to you ‘welcome and I wish you blessings, and I hope you bring your blessings into the space,’” Neckles mentions.

Shervone says her great great grandmother loved the song Bless This House so much that she made sure she taught all her children how to play this song on the piano and sing this song, and it was sung at every family gathering.

“When we say family heirlooms, we always associate it with objects that get passed down from generation to generation, but there are things that also get passed on like ways of being and knowing,” Neckles shared.

Growing up in a very Caribbean household, Neckles says she was surrounded by a lot of creative folks and creative energy but doesn’t think her family saw themselves as artists.

“Creativity is just something that’s integrated – it’s like you breathe it,” Neckles recalled. […] “My family’s from Grenada, when they migrated to the states, we grew up in a very Caribbean pocket of Flatbush Brooklyn, so I was also surrounded by that.”

Neckles appreciated the creativity and resourcefulness that she was surrounded by and it has always stayed with her, she said. She drew inspiration from her surroundings, from the way her family talked and dressed to the way their houses were decorated. It wasn’t until middle school that the idea of a career as an artist was introduced.

“My parents did take me to museums, but it still didn’t translate as something I could do,” Neckles explained. […] “That’s how art was introduced to me – a way of being. And later on, I was able to connect that with actually […] living as an artist.”

Neckles took advantage of the free art programs around New York while in grade school. She says it was the teachers in those programs who introduced her to the fact that she could possibly make a living as an artist

“They acknowledged that I had something and that I should actually continue to engage it and take it seriously,” Neckles remarked.

There was a resilience, toughness, optimism, and style about Brooklyn that Shervone grew very fond of. She said that being exposed to a space with range played a key role in her development.

“Brooklyn shaped me,” Neckles declared. […] “A few blocks away you’re in another neighborhood, with another culture, another type of food, another way of being – you know? I appreciate that.”

Neckles puts that love for finding oneself within a home into her work.

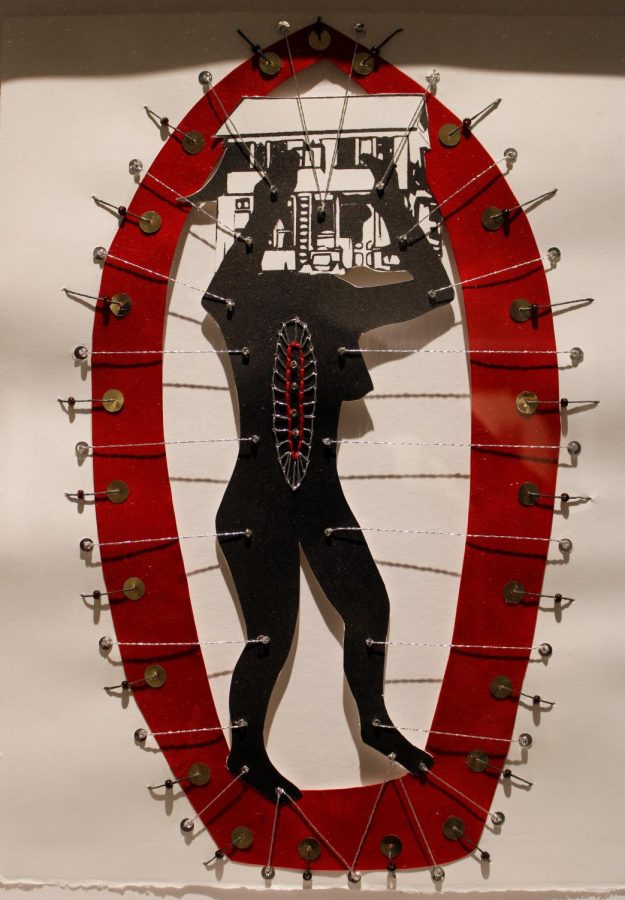

When discussing Neckles’ series Provenance, she mentioned Toni Morrison’s Beloved, a novel about a family of former slaves whose home is haunted by a spirit.

“There is a quote in that book where she [the author] says ‘freeing yourself is one thing. Claiming ownership of that freed self is another thing’” Neckles shared.

Besides identity, she said that the series is about liberation and ownership. She ornates different mixed-media materials from her environment and lived experiences on a repeated figure to explore what freeing oneself looks and feels like.

“What’s happening in the work too is making peace, making sense of […] these cultural norms that I don’t fit, don’t accept, want to undo, and then create anew,” Neckles elaborated. “So that’s what the work is going through.”

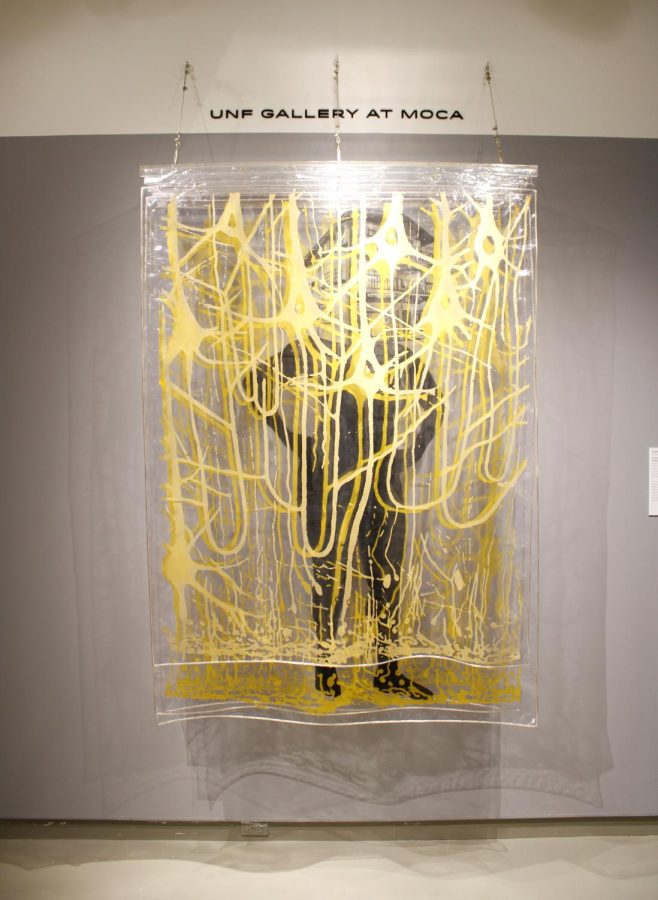

The following works portray photographs of Neckles’ maternal grandparents’ home and journal entries from family records onto vinyl, a similar material to the plastic coverings used to protect furniture from dust and wear, and create these ‘vessels.’ The installation casts cryptic shadows that add a layer of mysticism to the work.

Neckles said that she was thinking about her great-grandmother and when she was born (1904) and why the song Bless This House resonated with her so much.

“What I realized is that she had encountered was World War 1. […] But I was also thinking about that in Grenada, you are surrounded by elders. […] If she was born in 1904 and slavery on the island of Grenada ended in 1834 […] that means there were elders in her community that once had been enslaved. […] So I was thinking ‘Why that song meant that to her?’ Because of what is her lived experience.”

Neckles explained that her grandmother lived through the Cold War, The Great Depression, and Labor Rights in the Caribbean. She said her mother’s generation lived through Civil Rights, the Black Liberation Movement. Women’s Rights. The Vietnam War. Neckles also spoke about how her mother spent her childhood experiencing the transition of Grenada before and after its independence and lived through the revolution on the island and the U.S.’s invasion of Grenada.

“You can think about what you’re going through right now,” Neckles continued. “Look at our lived experiences. Coronavirus, all the racial injustice, all the police violence, economic/social/environmental issues. […] So what I wanted to do was compress that history of together, that lineage of us together,” Neckles explained.

Neckles continued to explain the meaning behind some of her materials and how that elevates the work.

“I’m also using that clear polyvinyl material because that’s the way we protected and cherished the things we loved back in the day even ‘till this day,” Neckles commented. […] “And so wanting to use that material to also talk about how we preserve ourselves and our stories, and it’s also about me being a custodian of this history too. It’s how I’m making sure that our story’s not lost.”

This self-portrait portrays Neckles with a house on her head immersed in neurons that are representative of the interconnectedness she feels to Grenada.

“When my parents decided they were going to leave Grenada, […] and made New York a home, […] they internalized Grenada, came to the states, carried it with them, and when they had me, they passed that yearning onto me,” Neckles said. “I inherited that from them.”

That yearning is something Neckles wants to convey – a longing for home, searching for a home, and carrying of home that adds another layer of connection in the work.

Neckles’ work is in conversation with visitors about home. She hopes to expand the conversation on where home really is.

“Home is a location, it is a physical structure, but then there’s also other layers of home that I’m addressing,” Neckles explained. “The home within us, the home we carry with us, the homes we occupy or enter. But really the conversation about what home really means.”

Neckles encourages young college artists not to limit themselves to only art-related things. She also says don’t limit yourself to materials. Always be open to trying new things, exploring, asking questions, and experimenting. Leaving home and spending time in other places can help you have a better understanding and awareness of yourself, Neckles adds.

“Part of being an artist is to be an observer of the world and to respond to the world around you, so that means you need to be an active participant and learner in the world,” Neckles stated.

Shervone Neckles’ exhibition is currently on display at the MOCA for all UNF students, admission into the museum is free, and they can bring 1 guest. Neckles’ collection will be available to view until March 5, 2023.

___

For more information or news tips, or if you see an error in this story or have any compliments or concerns, contact editor@unfspinnaker.com.