Conversations on sexual ethics are a staple of college campuses.

In the ‘70s it was Roe v. Wade. Then it was Sandusky. Today it’s the University of North Carolina.

UNC recently joined the conversation when a group of students filed a complaint with the U.S. Department of Education claiming the university routinely mishandled reports of sexual assault.

The university responded by threatening the expulsion of a sexual assault victim who spoke out against abuse.

Nationwide, university administration and students alike are witnessing a public conversation about how sexual assaults on campus are handled — because, unfortunately, sexual assault isn’t an uncommon problem.

According to the Federal Bureau of Justice Statistics, the estimated annual rate of sexual assault is between two to five women for every 1,000. Given the number of students who live on campus at UNF, this would amount to approximately 11 sexual assaults a year on campus, and 46 off campus, based on enrollment.

What’s more, according to the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control, 79 percent of rape victims are under 25 years old, which places college students at a higher risk.

So how many sexual assaults have been reported to university police at UNF this year?

One.

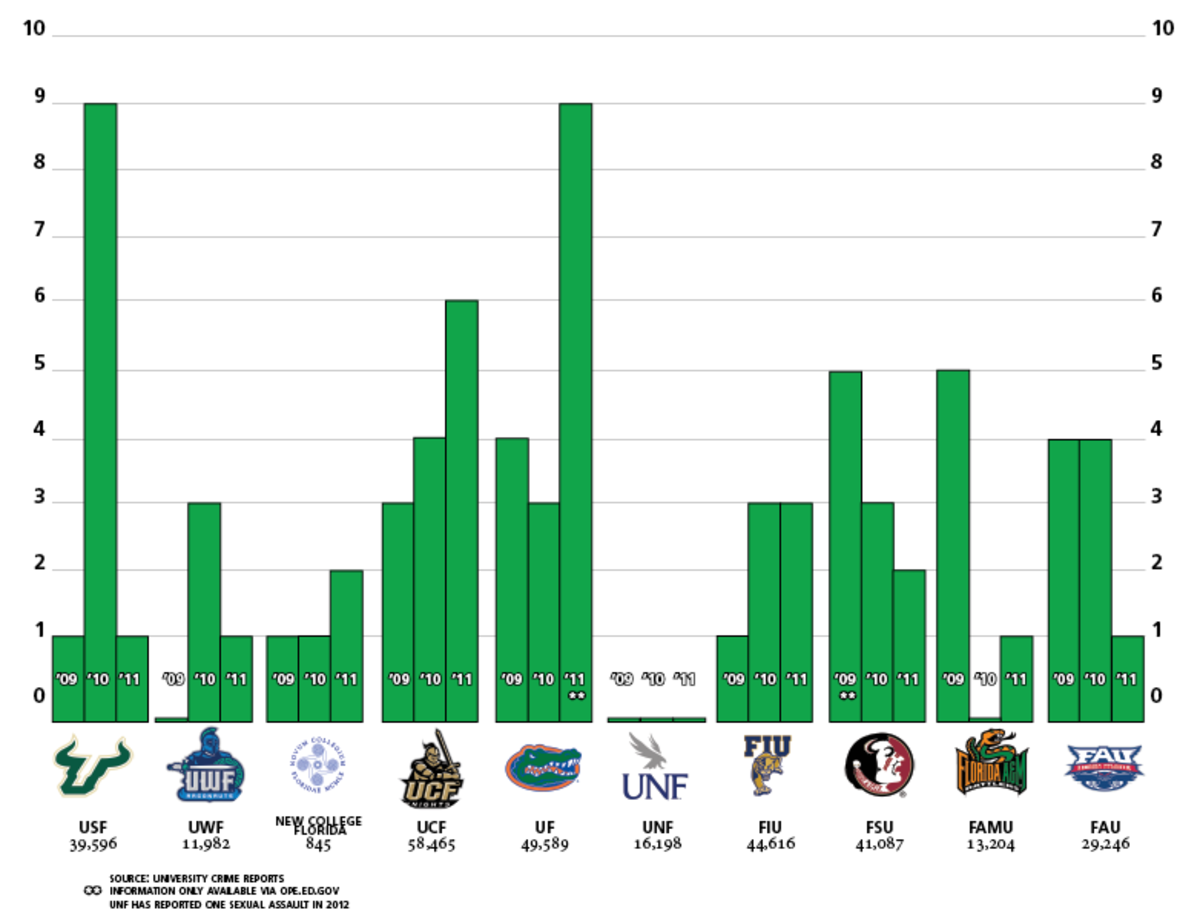

In fact, only one count of sexual battery has been reported to the University of North Florida Police Department in four years— the lowest rate in the Florida public university system.

The numbers don’t end there.

In the past four academic years, the UNF Women’s Center Victim Advocacy Program has assisted 62 UNF students who said they were the victim of sexual assault.

Sixty-Two.

The cause behind that gap is as multifaceted as the crime itself.

What does “rape” mean?

Terms like “sexual misconduct,” “rape,” “sexual assault” and “sexual battery” are often heard by students interchangeably — but they can mean different things.

“There are so many words,” said Sheila Spivey, director of the UNF Women’s Center, which operates independently of UPD. “Sometimes they don’t really mean the same thing.”

Rape is sexual contact without consent, Spivey said.

Spivey went on to say that consent cannot be given if a person is asleep, unconscious, or under the influence of drugs or alcohol.

“Anything short of a yes means no,” Spivey said.

The term used by the state of Florida, and thus UPD, is “sexual battery.” Sexual battery is non consensual “oral, anal, or vaginal penetration by, or union with, the sexual organ of another or the anal or vaginal penetration of another by any other object.” This means penetration by the hand or of the mouth could result in a rape charge equal to that of conventional intercourse under Florida statutes.

Although there is a wide array of language used in sexual violence, officers are trained to help victims through the reporting process, UPD Lieutenant Andy Joiner said.

UPD’s jurisdiction only includes incidents on or within 1,000 feet of UNF property. Joiner said if a student came to UPD about an incident off campus they would help them process the information through JSO.

UNF students are also protected by Student Conduct, which protects against “sexual misconduct and harassment.” This can range from harassing language to rape.

In the past four academic years, two such cases have been handled through Student Affairs.

“Sexual violence can occur on a continuum,” Spivey said. “It can range from behaviors that are intimidating all the way to behavior that’s terrifying.”

Florida law says people under the influence of alcohol cannot enter any legal contract, including agreeing to sex.

The Handbook for Campus Safety and Security Reports used by UPD offers strict definitions of what constitutes “forcible sex offenses.” It even offers scenarios that give framework for judgement calls by officers, such as: “A female student reports that her ex-boyfriend had sex with her in her campus residence hall while she was unconscious after a night of drinking alcohol. Classify this as one Forcible Sex Offense.”

The numbers

The Clery Act outlines the exact obligations of university police departments to keep students up to date on campus crime.

The Clery Act is a federal law enacted in 1990 that requires all universities that accept federal financial aid to report sexual assault crime data both to students and the DOE.

The law was put in place with the assumption that students could react and be safer as a result — so UPD has an obligation to notify students in a timely fashion.

In August 2012, UPD posted neon fliers labeled “Crime Report” across campus after a girl claimed to be sexually assaulted in the Wellness Center.

When UPD discovered that no assault took place, the report was labeled as “unfounded” and the student was charged with filing a false police report, so this number would not be reported to DOE.

In the event an investigation is still active, the incident is still counted in the Clery numbers, as shown in the April 15, 2012, incident involving a then 17-year-old girl. A year later, no arrests have been made because of conflicting accounts of the incident to police. The case remains open and is the sole report reflected in UPD forcible rape numbers.

University police departments are required to compile the number of forcible rapes and make those available to the DOE, information that becomes available on the department’s website. The crime data also become available to students through the schools’ safety guide.

UNF has only one reported case of rape in the numbers reported to the DOE.

An investigation of police reports for the last two years, cross checked against UNF’s Safety Guide and numbers reported to DOE, shows only the one. All the numbers match.

The same cannot be said of Florida State University and the University of South Florida, where the Spinnaker’s analysis of the information provided on the DOE website shows more forcible sex offenses than the crime reports on the respective university safety guides.

According to federal law, each violation can result in a fine up to $25,000.

The problems with reporting

Not everyone who is a victim of a sexual assault will report it.

The U.S. Institute of Justice found that only 18% of rapes are reported to law enforcement — thus, many will never go through UPD.

“We also understand that someone might not want to come forward and tell what happened,” Joiner said.

What would prevent someone from seeking justice?

Aubrey Moore works with sexual assault victims in the Jacksonville area and said the media play a part in affecting what people view as rape.

“It’s not that stranger who jumps out of a van and attacks someone,” Moore said. “In reality, most of the victims know the assailant.”

The reality is far scarier.

The Federal Bureau of Statistics reported that between 2005 and 2010, 78 percent of female victims knew their attacker — meaning a student may be safer walking home from a party in the dark than at the brightly lit party she was leaving.

Moore said many incidents of sexual violence don’t make it to trial because of hold ups along the way. This lengthy process can deter victims.

Cultural beliefs about the justice department can also determine if a victim reports a crime to police.

“In some communities, law enforcement may not be viewed as someone you call for help,” Spivey said.

Spivey said some cultures have an attitude that the community takes care of itself, while other cultures don’t bring up sexual violence.

Because of the inherently private nature of sexuality, students often don’t know what is normal because sexual experiences are not always openly shared with peers.

“I think most people know when something wrong has been done to them —you might not know the exact crime legally,” Joiner said.

What happens when it’s mixed with alcohol?

Adding alcohol makes the issue even murkier — especially when the negative stigma of under-aged drinking is added. If she feels guilty for drinking, a victim may feel she is not in a place to bring up the wrong done against her.

When the Department of Justice researched college incidents categorized as rape, only half of victims perceived they were raped.

One UNF International Studies major who wished to remain anonymous said there was an incident involving alcohol where things went much farther than she wanted to, but she took responsibility for the incident because she willingly drank.

Even amid the numerous education programs in both the UNF and Jacksonville communities, confusion remains about what rape is.

“People think of the textbook version of rape and don’t understand the different nuances of it,” said Anna Hixon, assistant state attorney in Jacksonville.

Hixon participated in the UNF Mock Rape Trial this month, in which legal professionals from the community acted out a sexual assault trial involving rape. The case involved an intoxicated victim who met someone at a bar.

When asked to vote, the UNF students in the audience didn’t all consider the incident rape.

“If someone has sex when they were too drunk to give consent, that could arguably be a crime,” Hixon said. “But they don’t think it is — so they don’t report it.”

The Shame Factor

Even when people do know for sure, they’re often unwilling to talk about it.

Ivy Crosby, a senior Psychology student, has seen the effects of sexual violence on women through working with the Hubbard House, a location for victims to confidentially seek solace from their attacker.

“They are in a dark place,” said Crosby, who’s done outreach at the Hubbard House as a member of Alpha Chi Omega.

Crosby doesn’t think the UPD numbers accurately reflect the number of rapes at UNF because “victims of sexual violence are scared to report or ashamed to report.”

“Knowing the girls that I know, if everything were reported I think one sexual assault is not at all an accurate representation,” Crosby said. “I think it’s a lot more.”

What does it mean?

The chasm between reporting and reality is not without consequence.

Studies out of the University of Massachusetts and the U.S. Navy have provided some dramatic insight into those committing sexual assault.

David Lisak asked male university students if they had ever used force to engage in sexual activity or had sex with someone too intoxicated to resist.

Six percent said yes. Of those, 60 percent said they did it more than once.

The U.S. Navy later duplicated the findings in a subsequent study.

If the same individuals are committing sexual assault and getting away with it, even if the victim feels satisfied with the outcome of care and counseling — is that good news for campus safety?

“We have to look at the issue of silence,” Spivey said. “Rape is a crime that takes away a victim’s voice.”

In the current set-up, when a voice isn’t raised — can’t be raised — it could mean another voice is silenced.