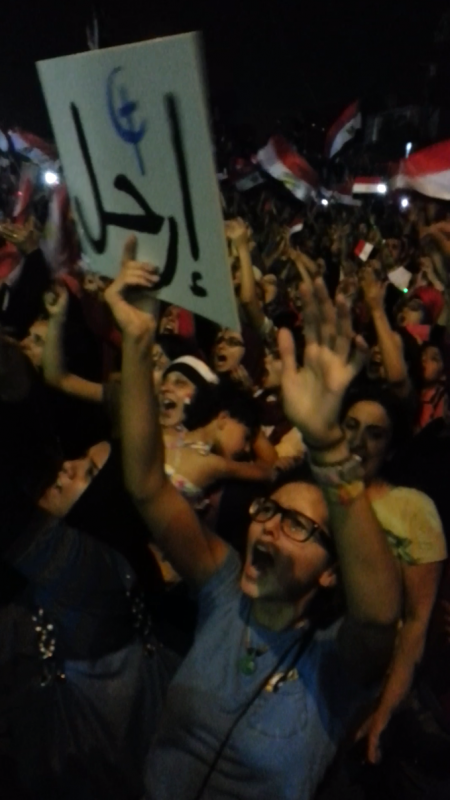

Lydia Moneir holds a sign proclaiming, “Leave” with a combined crescent moon and cross representing both the Muslims and Coptic Christians involved in the protests.

Lydia Moneir, daily news editor, shares her thoughts and experiences as an Egyptian facing a second revolution.

A few weeks before the demonstrations, I pulled into a gas station – there was no gas. A man who worked there said I should try two places nearby; both gas stations were dry.

“Morsi is going to make beggars of us all,” he said.

Egypt is half a world away from most of the people reading this, and I can’t convince you to care about what happens to it. I can say that the Egyptian youth have proven that they will consistently organize to reject any authoritarian government forced on the nation— showing that movements from the people have power.

Maybe this mass of demonstrations came as a surprise to the rest of the world, but it was clear to me that things had gotten significantly worse since I was last in Egypt. Power outages and fuel shortages plagued the country, and everywhere I went people grumbled about Morsi destroying the country.

In the year that Mohamed Morsi ruled as president of Egypt, the economy worsened with out of control inflation and skyrocketing prices, people were imprisoned for insulting Morsi, and there were several attempts by Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood to create an Islamist stranglehold on the government and country.

So I wasn’t surprised when I saw posters urging people to protest against Morsi covering almost every flat surface in Cairo at least a month before it all happened, all with the date of June 30th, marking one year of Morsi’s rule.

Building Tension.

One of Morsi’s most controversial moves came in November 2012, when he issued a decree that fired Egypt’s attorney general and gave the president sweeping powers, including the right to make decisions that were above all levels of judicial review.

This decree was rescinded after major street demonstrations and outrage from the Egyptian people, but the balance of power in Egypt continued to tilt towards the Muslim Brotherhood and other Islamist parties.

There are two houses of parliament in Egypt – the House of Representatives, which is meant to play the more important role in drafting legislation, and the Consultative Council, which had limited powers. However, the Supreme Constitutional Council (SCC) ruled that the Islamist-dominated House of Representatives election was invalid due to fraud so it was dissolved. Without the House of Representatives, the majority Islamist Consultative Council had more legislative power by default until new elections could be held.

Mohamed Morsi’s face is crossed out on a poster that reads “The Brotherhood’s Occupation Ends June 30” calling for rebellion on the one year anniversary of Morsi’s rule.

The new constitution was written and rushed through by the Consultative Council, even after secularist and non-Islamist members of the assembly walked out –some leaving the council altogether– in opposition to it because many of the laws were seen as Islamist and oppressive to women, secularists and Christians.

A referendum passed the constitution, with a very low voter turnout of 32.89 percent. At the time, many who had supported the Muslim Brotherhood felt betrayed by their actions since taking power, but felt that voting “no” would be siding with the opposition, which they didn’t support either. Many others simply felt disheartened by the clear move away from democracy and felt that voting in itself had no meaning. Opposition members also told people to boycott the vote because those who wrote the constitution did not represent Egyptians as a whole. Now Egypt had a broken government and a flawed constitution that did not represent the people.

Two weeks before the looming demonstration date June 30, Morsi gave a speech, surrounded by his supporters. He sat on the podium by men who had previously been tried and imprisoned for terrorism and pardoned by Morsi.

The Muslim Brotherhood’s Mufti – interpreters of Muslim scripture – announced on-stage that protesters against Morsi were not real Muslims, but infidels. Many Egyptian news pundits expressed shock over this, and other things said by their Islamist fellows on stage, which were thinly veiled threats of violence against protesters.

The Muslim Brotherhood frequently attacked protesters’ faith, fueling the anger of many moderate Egyptian Muslims who felt as if they were being threatened into silence.

With Islamists holding powerful positions they had little or no right to —and opposition either being ignored or met with threats and imprisonment— the Egyptian people were left without a democratic process to stanch the flow of the Brotherhood’s growing power.

So they took to the streets.

On July 1, I attended a large demonstration at the presidential palace in Cairo. The streets were clogged with people and cars, Egyptian flags waving in so many places it was as though Cairo had been painted red, white and black.

As I walked through side streets to get to one of the larger protests at the Presidential Palace, people streamed back and forth from the demonstration, with signs exclaiming, “leave” to Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood, with their children hoisting flags. Reacting to the Muslim Brotherhood’s elitist and discriminatory mutation of Islam, people chanted that Christians and Muslims were all Egyptians, carrying a popular emblem of the Muslim crescent moon and Christian cross combined.

In a speech on live television the next day, Morsi’s reaction to protests was to insist his presidency was democratic and legitimate, and thus indisputable. He offered protesters no concessions and rejected the military’s 48-hour ultimatum to reach a compromise agreement with the opposition.

Back in 2012, Morsi won the presidency with only a 3.5 percent margin against a member of the old regime that had just been toppled. That was before Egyptians had any experience of what it was like to be ruled by the Muslim Brotherhood, a party that had been illegal in Egypt since 1958, when the Brotherhood was convicted of attempting to assassinate the then secular leader of Egypt.

Not only was Morsi’s victory a slim one, but it also stank of fraud – pre-marked ballots were discovered, presiding judges were found to be fake, and the Muslim Brotherhood gave money and food to the poor of Egypt’s countryside and then bussed them to voting stations.

So much for Morsi’s indisputable legitimacy.

Things heat up.

Protests continued. Anti-Morsi protesters waited for the military to act, some standing in front of their headquarters and calling on them to intervene.

On July 3rd, Defense Minister Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi gave a speech announcing the end of Morsi’s presidency and describing the military’s “road map” that would carry Egypt through this transition period.

People of every conceivable demographic took part in the celebrations; these older men brought a make-shift sitting room with them.

As soon as he finished, I heard cheers and fireworks even on my quiet, residential street. Al-Sisi announced that the chief of the SCC would take over as acting president, the constitution would be suspended and a technocratic government would be installed until early elections could be held. A technocratic government would mean that decision makers would be selected based on their technical skill and experience in the field. While this could be a problem depending on who does the selecting, it is meant as a temporary transition before the next election.

I went into the streets that midnight and the celebrations were still going strong. Families came together, waving flags and swinging children between their arms. Old men sat together drinking tea, one with a sign around his neck that said, “Bye bye Morsi.” Young men loosed fireworks and yelled.

I found myself stopping to take photos and videos wherever I went, astounded at the sheer mass of people thrumming in the streets; I could feel the heat coming off the crowd. A woman helped me get up on a truck to take photos and smiled at me the same way everyone was smiling – from one Egyptian to another, bright-eyed, triumphant.

Egypt’s military.

Many outside of Egypt instantly labeled this a military coup, but it is not that simple. Perhaps this is because some American and British media outlets portrayed pro-and anti-Morsi protesters as being approximately even, describing Egyptians as “divided.”

But this is far from the truth. A total of 22 million Egyptians signed the petition put forth by the movement, “Tamarod” – “Rebel” when translated to English – that urged people to demonstrate. In a country of about 84 million, between 16 and 33 million people actively came out against Morsi in the week before Al-Sisi spoke, compared to the mere thousands that supported Morsi even after he was ousted.

The military would not have acted had it not been for the millions who took to the streets against Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood. They were welcomed by the Egyptian people, and have long been seen as a force of the people, not the government.

This may be because the Egyptian military is large enough and powerful enough to basically be a self-governing entity. With about $1.3 billion in aid from the US every year that accounts for approximately 20 percent of its budget, the Egyptian military is a force to reckon with. They didn’t take control, they gave control to a civilian interim government.

Many are asking, why would Egyptians be happy to see the military intervene?

Maybe it is because with conscription still active – requiring at least one year of service from all Egyptian males over 18 who have at least one brother – the majority of Egyptians have ties to the military in one way or another. Maybe it’s because the military had control in between Mubarak’s ousting and Morsi’s election and relinquished it. Maybe it’s because, although Defense Minister Al-Sisi is wildly popular and could have appointed himself interim president, he and several representatives of the opposition chose instead the leader of the SCC, a court that has continued to curtail Morsi’s power grabs over the past year.

The red writing next to the graffiti faces says “blood for blood” and “slam ya 5aroof” written in English means “goodbye, you sheep.”

One thing is certain – the majority of Egyptians see the military as a tool of the people, and the military’s actions as representative of what the people want. The military acted in accordance with the protesters’ demands.

Although historically military force has not often been associated with democracy, it is the military that is attempting to and succeeding in preventing violence on the streets, and it is the military that is carrying out the wishes of those millions who yelled for and end to what they called the Muslim Brotherhood’s occupation of Egypt.

America & Egypt.

Since the Camp David Accords that brought peace between Egypt and Israel in 1978, the US government has given Egypt an average of $2 billion a year as part of the agreement. This made Egypt second only to Israel in terms of receiving aid till 2002, but it still remains in the top four. Because of this, Egypt has long been the most stable and reliable Muslim ally to the US.

Many Egyptians have criticized aspects of this relationship over the years, saying that Mubarak and then Morsi were America’s puppets. Although the US government openly supported 2011 protesters once it was clear Mubarak was on his way out, it does not change the fact that consistent aid was given to Egypt’s government when it was obviously a dictatorship.

It has not helped that, despite a clear and rising tide against Morsi —and obvious moves by the Muslim Brotherhood to tighten their hold on Egypt through undemocratic moves—the US government turned a blind eye and continued to praise Egypt’s new-found “democracy.”

Egyptians do not have any particular animosity towards Americans. There will always be some extremists with irrational hatred in any country, but for the most part, Egyptians can distinguish between the American government and the American people.

Between 16 and 33 million were involved in demonstrations during Egypt’s second revolution in three years.

Anger from the Egyptian people stems from what they feel is US meddling in Egyptian affairs. I am guilty of the same thing, because when I saw on the news that President Obama was urging Egyptian restraint and an adherence to democracy, I asked, “What business is it of yours?”

Many Egyptians are angered at how recent events are being portrayed – certain things are emphasized, others left out. As I write this, many Morsi supporters have announced a Jihad on anti-Morsi protesters, a church and a Coptic settlement have been burned. It was clear from watching Egyptian news channels and listening to what Egyptians said in the streets that the majority of the violence has stemmed from some of the extremist Islamists among the pro-Morsi protesters, yet this was under-reported.

I believe that while relations between Egypt and the US are strained right now, the best thing for the US government to do is back off when it is clear that Egyptians do not want American involvement. The most important thing to Egyptian people on a day-to-day basis is ensuring we have a democratic, representative government, a stable economy and a stable country.

If the US government is concerned about the welfare of the Egyptian people, do not send military personnel — send aid. This is how to garner the appreciation and respect of the Egyptian people. Send fuel, send food, send medicine.

Coup: the simple word, the complex reality.

Coup— this one word wrongly reclassifies what is happening as non-democratic — despite the fact that the number of people protesting against Morsi was larger than the number of people who voted altogether in 2012’s election.

The Egyptian flag is waved on July 4. A translation of a common chant of protesters is “Raise your flags of victory, tonight we govern Egypt.”

Furthermore, the military did rule Egypt through the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) after protests forced Mubarak to step down in 2011. Why was this not classified as a coup?

Had the military acted of its own volition, it would have been an outright coup. As it was, they responded to the millions – let me say that again, millions – of Egyptians who took to the streets.

The military gave Morsi a chance to respond to protester demands, and he did not. They acted with the support of the Tamarod movement’s leaders, the Coptic Pope, the Grand Sheikh of Al-Azhar Mosque – a highly respected Islamic institution – and Nobel Peace Prize winner and Egyptian law scholar Mohamed ElBaradei, who is being considered Prime Minister.

That is not to say that I and other Egyptians are not wary of the Egyptian military’s swift power. Many think that this “road map” they presented was formulated so well, it had to have been planned well in advance.

There has also been criticism of the military’s shut-down of Islamic TV stations. Immediately after Al-Sisi announced that Morsi had been ousted, many Muslim Brotherhood supporters on television called for blood. Because of this, many believe the military’s actions were an attempt to quench violence from pro-Morsi demonstrators.

Whether it is that simple or their reasoning was more nefarious, only those high up in the military can tell. As it stands, however, the military has not seized power, but handed it over to others deemed more fit to represent Egyptians before elections.

Egyptians will not stand by if they think their revolution is being stolen once again. The seal has been broken, the path of demonstration well-worn, and Egypt may well be on its way to developing a stable democracy.

Egypt is a unique Muslim country, its people have always been moderate, and its policies progressive, particularly when compared to other Arab nations. Now that the Muslim Brotherhood has shown its true face in Egypt and more representative groups have had time to organize, I have hope for a more inclusive government in Egypt’s future.

For those who say that a true democracy would mean people waiting three years till the next election, I say this: at the rate Morsi’s government was going, there might never have been more elections. When members of the government continually ignore the words of their citizens and put their own desire for power over the needs of their citizens, they risk forfeiting their elected positions.

Democracy is not a ballot box. It is the voices of the people being heard and heeded.