It is a busy time at UNF and other colleges throughout the country. We are just a few weeks into the fall term, and students are just now settling into their classes and extracurricular activities.

An NPR article published on Sept. 8 characterizes how females are now in “the red zone,” which is described as “from the first day on campus to Thanksgiving break — when female students are thought to be at higher risk of sexual assault.” The article says there is no evidence supporting this common misconception, but it is just one of many surrounding the idea of sexual assault and rape on college campuses.

There has also been a lot of recent coverage of Emma Sulkowicz, a student at Columbia University, who has been carrying a mattress around her campus to symbolize the weight of what she has been dealing with — an alleged rape and an improper response from the school.

She will not stop this performance art piece, as she calls it, until she graduates, unless her school expels her assailant. Two years after being raped on the first day of sophomore year, Sulkowicz is now a senior and her assailant still walks the campus. Two other students have come forward and accused him of the same thing, and still the school has not taken any action against him.

This kind of non-response from the university is typical. We live in a world where victims are questioned and assaults are swept under the rug to protect those who committed them. It is unfortunately a very common mindset, as made evident by the negative comments under stories like the one about Sulkowicz. Mixed in with the expected support and positivity, attacks on her motives are brought up by people who question whether or not she was even raped.

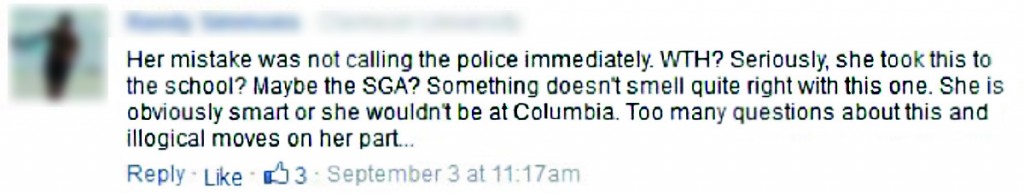

“Something doesn’t smell quite right with this one,” someone commented on a Huffington Post article about the Columbia student. “She is obviously smart or she wouldn’t be at Columbia. Too many questions about this and illogical moves on her part…”

Comment taken from Huffington Post article

Comments like these are part of a nasty habit of blaming the victim, an issue that has become increasingly noticeable in the open forum of internet comments. Ambivalently, this raised profile has cause people to begin labeling society’s response as “rape culture.”

Rape culture is something that happens when the media and other facets of society excuse and normalize sexual violence against women. This is caused by a multitude of things — the way women are portrayed on TV and magazines, the way men are portrayed through the same mediums, how we frame the news, and the tendency people have to ask questions like, “What was she wearing?” and “Was she drinking?” instead of questions like, “Why did he rape her?”

The point that the media and its consumers often seem to forget: sexual violence is never the victim’s fault.

If someone got a hold of your bank account information, no one would say, “You shouldn’t have been using that bank. What were you thinking?” Instead, you would find sympathy and a timely and diligent response from the police. Why is it any different when people steal nude photos or rape women?

People know how it works, and this knowledge is one of the reasons why people do not report sexual assaults. Women who have been traumatized and violated know how traumatic it can be to go through the process of reporting the crime and seeking justice.

There are so many different stigmas that permeate our society from the day we are born, and they make being a victim into a shameful thing. Reporting a rape is an incredibly hard thing to do, so a lot of times people just do not do it. This does not make it their fault, but ours for perpetuating these ideas.

A 2013 Spinnaker article exposed the fact that in the previous four years, there had only been one case of sexual battery reported to UNF Police Department. In that same amount of time, the UNF Women’s Center Victim Advocacy Program assisted 62 UNF students who said they were a victim of sexual assault.

Additionally, the article informed students that only 18 percent of rapes are reported. These numbers tell the sickening story about how our society has a tendency to underestimate the significance of rape. When individuals do not feel comfortable reporting assaults, and the police have less than supportive responses, we are sending a message to rapists: there are no consequences. Continue to do what you do.

When we laugh at rape jokes, or say “That math test raped me!” we are normalizing rape. We are sending a message to rapists: I think what you do is okay.

When we tell women not to take nude photos or not to drink when they go out, we are sending a message to rapists: It’s their own fault, they brought it on themselves.

We need to consider whether or not these messages are ones we want to be sending. All too often people have a tendency to think that something does not apply to them — because they have never been raped, or because they are not a woman. But this issue affects men as well. Men who are raped have been socialized to think they’re supposed to love sex in all forms and should not complain. But a society-wide problem calls for a society-wide response.

UNF has recently taken steps in the right direction and amended its regulations on sexual misconduct. The revisions included adding dating violence, domestic violence and responsible employee to their list of definitions. The changes also clarified several definitions, expanded their sections regulating procedure and included a much longer list of resources for victims among other changes.

This kind of action is what we need if we want to be the culture we pretend to live in — intolerant of injustice and violence of all kinds, with no exception. Educating others and ourselves is key to this process. Next time you think about commenting something negative on an article about a victim, think twice. Think about what you’re doing, and don’t do it.

Email Cassidy Alexander at reporter8@unfspinnaker.com