With any form of art, there are works that are considered masterpieces. In the case of cinema, these are the films that are regarded as timeless by both critics and audiences alike- “The Shawshank Redemption” or “Citizen Kane,” to name a couple.

But no matter the medium, there’s always the occasional bizarre choice when you ask a critic to list their favorite movies. Films that are considered far from masterpieces. When I am asked to list my favorite movies, there’s a strange choice in between things like “Shawshank” and “The Room,” a film that holds a solid 26% rating on Rotten Tomatoes. It is by no means a perfect film- but it’s arguably one of the funniest things I’ve witnessed in my life.

There is an art form to making a terrible film, one that meets the perfect storm of awful acting, directing or budgeting. We’ve all heard of these films- they’re the ones which are so awful that you can’t help but laugh at them. They manage to go beyond a normal bad film and become something special.

With that in mind, however, why are some bad films loved more than others? For this, we need to refer back to the unique aspects of a ‘so bad, it’s good’ film and how it differs from a standard box office blunder. There is a clear line between what makes a film ‘so bad, it’s good’ and just a product that is ‘bad’: primarily, this comes from the bizarre and unique ways in which many of these films manage to fail.

Generally, in the case of humorously horrendous cinema, the unique ways in which “awful films” are horrendous can transform terrible film into something more than just a flash in the pan- and in some cases, become even more memorable than a film of much higher quality.

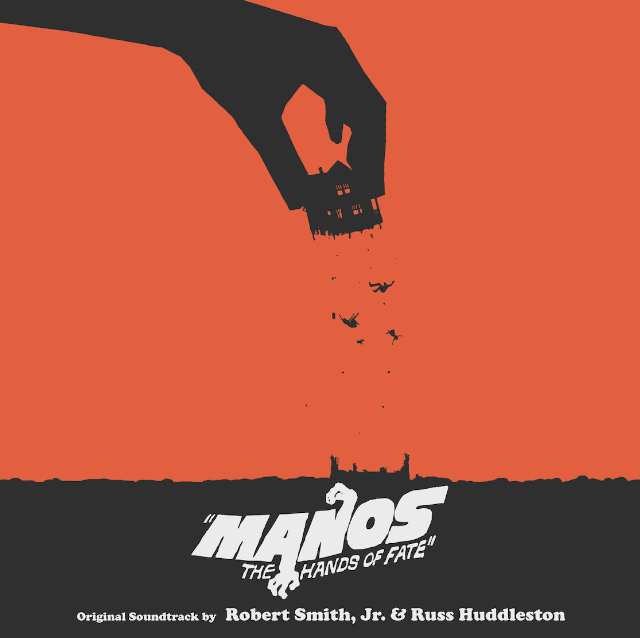

Let us take, for example, two films currently sitting comfortably as two of the 100 lowest-rated films on IMDB: “Disaster Movie” (which, at time of writing, is the lowest-rated movie on the site), and “Manos: The Hands of Fate” (currently the third-lowest).

If one goes by ratings alone, then from a logical standpoint “Disaster Movie” is the worst movie- but if this is the case, why do we celebrate “Manos” as a hallmark of terrible film making and leave “Disaster Movie” to gather dust? It is because of the unique circumstances and results that spawned from the making of “Manos,” all in all leading to a more memorable and uniquely awful picture that is unlikely to be found in any other film.

The idea of watching a project fail in a unique and spectacular way is what can make the difference between something forgettable and something awfully memorable. At times, even the background of a film can make it infinitely more enjoyable than something standard-issue. Which of these two films would you, for example, prefer to see a film about the making of?

“Disaster Movie,” which was produced in a normal Hollywood studio with the latest camera and lighting technology, had typical special effects as well as a $200 million budget. The film was released to nationwide theaters. Stories from the film’s premiere include: The film not being screened for critics, and the first on-film appearance of Kim Kardashian (I’m being serious. These are the only stories from the set I could find).

Or “Manos,” a film which was created on a bet from the insurance salesman director with a budget of under $ 20,000, no special effects, and a handheld camera that could only hold 32 seconds of film at a time. The film played once at a local theater in El Paso. Stories from the film’s premiere include: One actor being high on LSD during filming, only two actors being paid (with a bicycle and a bag of dog food), and many of the film’s cast and crew sneaking out of the theater to avoid having to admit working on it.

When we look at the unintentional successes of projects such as “Manos,” it’s understandable why people would flock to something more interestingly terrible than a standard run-of-the-mill bad film. People like to laugh at larger-scale mishaps more than smaller ones. All comedy is based off of misery, after all, and more misery tends to lead to more comedy.

A parody movie like “Disaster” may fail simply because it made very little money, but the legacy a truly terrible film leaves after you sit through it will stay with you. It’s the one you’ll quote with your friends and family long after you’ve forgotten the bad pop culture jokes or stunts of a typical film.

In a way, perhaps the making of a truly horrible film is a sort of awakening for both the director and the directors of the next generation- as some sort of bizarre reminder of how not to make a film.