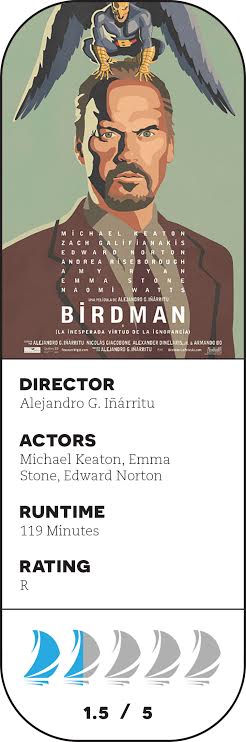

Note: this review was written before Feb. 22. It is not a response to any awards, although Spinnaker did correctly predict the film’s Best Picture, Best Original Screenplay, Best Cinematography and Best Director awards Sunday.

In Hollywood, there is meaning in every shot of film in a movie. The director chose to shoot each scene a certain way. This doesn’t mean every take is a grand artistic statement. It could just be that the day was ending and the sunlight was running out.

Sometimes, however, when you look deeply, you end up seeing nothing at all. The abyss stares back, as a nihilist would say. This, I found, was the case with Birdman¸ the latest film from Alejandro González Iñarritu. It was a case study in vapidity.

Birdman concerns Hollywood actor Riggan Thomson (Michael Keaton), who has undergone a quest to achieve some semblance of respectability as an actor, lost after years of doing “Birdman” movies. The actor does this by staging his own Broadway adaptation of Raymond Carver’s book What We Talk About When We Talk About Love.

The play, however, is a disaster, thanks mostly to the last minute hire of method actor Mike Shiner (Edward Norton). Shiner breaks character on stage and throws a tantrum when he finds out the bourbon he’s drinking has been swapped with iced tea. During the final scene of a preview, he finds himself aroused and tries to screw his co-actress, on stage. “It’ll be real,” Shiner repeats incredulously. They happen to be an offstage couple, but that’s no excuse.

On top of this, Riggan battles not only a New York Times critic with a vendetta against stars, but also his own failing psyche, as an inner monologue from Birdman keeps jabbering at him to give up and retreat to Hollywood. He also displays superpowers such as flight and telekinesis. Whether these are real or illusions is left ambiguous. All of this, in one single take.

Well, not exactly. To film Birdman, Iñarritu poached the great cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki, master of the long take and a frequent collaborator of Terrence Malick and Alfonso Cuarón. He and Cuarón both won Oscars last year for Gravity, which, unlike Birdman, is a good film. Most of Lubezki’s work here–which I blame on the director’s lack of creativity–involves claustrophobic tracking shots of the theater and its inhabitants, and the occasional look at the New York City streets. It’s designed to look like a single, unbroken take.

I would be fine with this approach if it amounted to something a little more interesting. The one-take approach was actually achieved a decade ago by Alexander Sokurov in Russian Ark, a history of Russia told with a time traveling tour through the Hermitage in St. Petersburg. It’s a flawed film, but I’d rather watch a camera stroll through a palatial art museum than a run-down theater.

Now back to the point of vapidity. That Michael Keaton–whom I do not mean to disrespect–is playing a version of himself is so incredibly obvious, they might as well just have used his name instead of a character. It’s the hook of the film: washed-out actor who used to be Batman plays washed-out actor who used to be (stock superhero name that starts with B.)

This is a dark comedy, but the film’s sense of portentous jadedness means none of its jokes land. Most of them are bait and switches wherein a white lie is either uncovered or told to either denigrate a character or make them feel better. One of these occurs when Jake, the play’s producer, tells Riggan that Martin Scorsese is in the audience. When asked if he really is by another actor, he replies “Yeah, and the pope too.” Zach Galifianakis delivers that line. Left on his own, he is a very funny man. Saddled by Iñarritu’s inane script, he becomes another instrument of mediocrity in a movie full of them.

Every actor in the film operates on the same note, making cutting remarks until they lose it and deliver a “defining” moment where they chew the scenery until their teeth fall out. Emma Stone has one as Sam, Riggan’s distant, dispassionate daughter and assistant. She castigates her father for putting on such a pointless vanity project of a play. Everywhere else, she’s pretty good. I found myself empathizing with her aloofness. Then Iñarritu has her shack up with Method Mike and we’re back to square one.

The film ends with Riggan doing something drastic on stage that inadvertently secures his place among the press and fans as a true artist. It’s actually a fairly meaningless act of violence misinterpreted by the crowd, but in Iñarritu’s world, that’s adequate enough. Thankfully, we don’t live in his world, and can rest easy knowing that both Riggan’s play and Iñarritu’s film suck.

—

For more information or news tips, contact assistantmusic@unfspinnaker.com; if you see an error in this story or have any compliments or concerns, contact features@unfspinnaker.com.