Coming of age is not restricted to one kind of person. Not just boys. Not just white people. Not just straight people. We all grow up, and we all deserve to have stories told about it—to see ourselves in those stories. Love, Simon, like more and more coming-of-age films today, understands this.

It’s not just about representation, though. It’s about the care and treatment given to characters of marginalized communities. Here, Love, Simon passes with a rainbow of color.

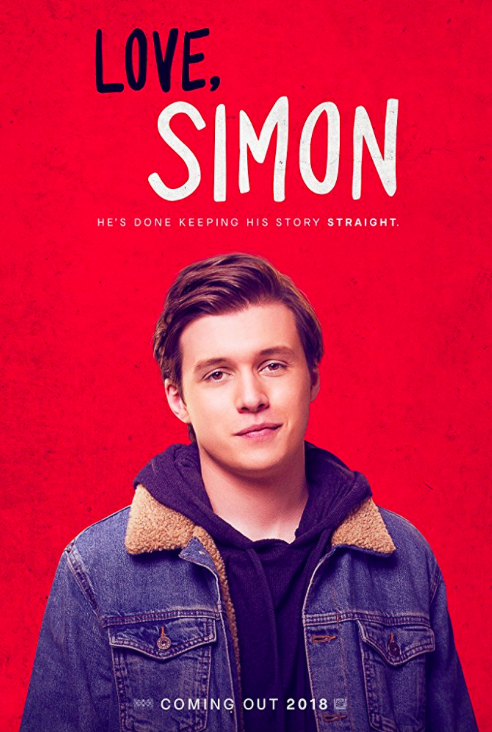

We happen upon Simon (Nick Robinson), a closeted suburban teenage boy surrounded by people who love him. He’s not the popular kid in school, but he has friends. In his words, he has a “perfectly normal life.” However, one would be making a critical error by concluding that this film is without struggle. The sheer difficulty of coming out is more than enough conflict to carry the story on its own, even if life is normal otherwise.

Simon, like many other closeted people, encounters numerous obstacles on his path to self-acceptance. This film, though, is also a journey through the aftermath. Over the course of this journey, Simon experiences threats, bullying (albeit slightly caricatured at times), and the destabilization of his friend group. Director Greg Berlanti shows how surprisingly easy it is to inadvertently hurt the ones we care about once a secret of that magnitude is set free. Simon is manipulated and put into precarious positions that force him to choose one evil over the other, and fear proves to be in command.

The complexity of the situation is masterfully revealed to those who may not be aware of it, as well as those who know it all too well.

Simon’s fully-actualized background ensemble allows others in the audience to be a part of the story, too. One might see themselves in Simon’s mother (Jennifer Garner), a loving woman who senses her son has a secret and battles her conflicting instincts to either pry or let it be. One might identify with Simon’s father (Josh Duhamel), an equally loving, well-meaning parent who burdens the guilt of past jokes and jabs making light of gay people and gay culture without thinking about who was listening. One might be the best friend, portrayed here by an incredible Katherine Langford, who wears her heart on her sleeve and must also navigate the abrupt shift in her closest friendship. Or perhaps you’re the villain (Logan Miller), and you’ve hurt a struggling human being without considering not only the person’s feelings, but also those of the countless others who would be affected afterward.

Background stories matter here (and in our own lives), and Berlanti pays attention to them. He also ensures that intersectionality has a place in his film by giving life to his gay characters of color.

Some optimistic elements of the story may be a hard sell for people who haven’t had the same luck. Simon is loved and supported by his family, friends, and eventually the majority of his school. When one character is bullied, he claps back with stinging words that draw praise from bystanders. This surely isn’t everybody in real life, and that’s okay. We don’t want to make the mistake of holding Berlanti’s film to the standard of portraying every gay person’s experience, which is an impossible task. We certainly don’t do that for heteronormative coming-of-age movies.

Berlanti takes that optimistic view and paints a beautiful picture that may look more real to some than to others, but the fact that this movie is hopeful is inspiring for many closeted people out there. Love, Simon is a beacon for those struggling with their identities. It’s a life raft cast out to sea for anybody in despair, searching the depths for the will to grab hold and continue on. It’s a therapy session for those who have lived through Simon’s life, or at least its central conflict. It’s a landmark cinematic achievement with the potential to do an infinite amount of good in a dark and dreary world.

I didn’t even mind the viewers around me “aww-ing” and cheering loudly during the movie because, to me, it meant that we really are changing. That a gay coming-of-age film can get that positive a reaction out of a general audience made up of men and women of varying ages shows significant progress. It is hope—an experience I can’t recommend highly enough.

Sails: 4.5/5

—

For more information or news tips, or if you see an error in this story or have any compliments or concerns, contact editor@unfspinnaker.com