Like all of us, Jacksonville also has a history.

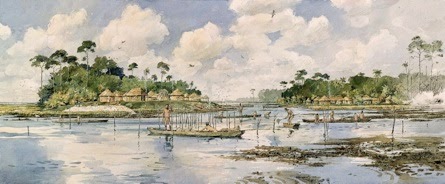

Once upon a time, this region was called Wacca Pilaka, by the Mocama tribe. It was part of a thriving Timucuan kingdom of some 200,000, and spanned 50,000 kilometers through North and Central Florida as well as Southeastern Georgia.

In the 1800’s British colonists arrived and Wacca Pilaka became Cowford, and then Jacksonville. By the 19th century, Jacksonville was becoming a retreat destination from the frigid winters of the North. This development was only halted by the great fire of 1901, which is still one of the worst disasters in Florida history. It was the third largest urban fire in the U.S. In 8 hours, the fire burned through 146 city blocks, destroying more than 2,368 buildings and leaving almost 10,000 residents homeless.

It was after this fire that downtown Jacksonville was rebuilt, taking on more of the shape that can be seen today. Architects from all over came in and left their mark on the Bold New City of the South. One such development was the Doro District.

According to The Jaxson, a multimedia project dedicated to urbanism and culture on Florida’s First Coast,

“The Doro block’s history dates to just after the Great Fire of 1901. The oldest building was built between 1903-1904 on the main commercial corridor of the East Jacksonville community in what’s now the stadium district. It was home to the George Doro Fixture Company continuously from 1919 to 2016, hence its common name. It may be the oldest surviving commercial storefront building from East Jacksonville, and is one of the oldest surviving buildings in Downtown.”

The buildings are currently slated for demolition. This decision comes on the heels of other demolition projects that have razed buildings and ruffled feathers.

“Cities that are the most vibrant and interesting are the ones that have a sense of their own history and identity and they value it,” Co-Founder of Jaxson and UNF alumni, Bill Delaney said. “A lot of it is relatively mundane on an individual level but all the pieces fit together to create something special, Jax has an opportunity to do that, we can preserve what we have and build new things. We can create something that you can’t get anywhere else.”

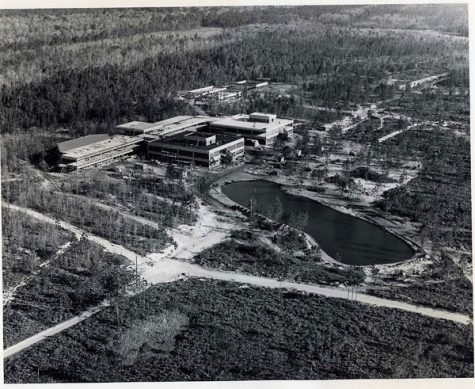

Students may be able to relate with this as a school’s history and campus culture often influence decisions to attend a particular school. Part of the draw for our school comes from UNF’s gorgeous campus, its rich history and the connection to it. Students go to college to be connected to a campus story that is bigger than themselves. In many ways, college campuses are like small cities of their own. The concept of finding your home within a university family is rhetoric many students are probably familiar with.

On a micro level, UNF has managed to elegantly build on its existing story in a way that continues to draw students in. Jacksonville too has an opportunity to recreate itself as a destination that stands out from the ‘prototype development’ which makes up an increasing amount of national cityscapes.

“Preserving a city’s existing historic structures is clearly the best path to creating an authentic urban fabric that tells a story that people will understand and appreciate,” Brandon Pourch, architect and member of the citizens group #mappingjax, said. “Architecture that is not related to the surrounding context of the city feels ingenuine and does not create a sense of place.”

Mapping Jax is not an official organization but rather a group of concerned citizens who share a similar vision for downtown. That vision for a ‘vibrant Downtown and a world class city of Jacksonville’ seems to resonate. There are currently over six thousand people in the Facebook group.

“Our work is important because the voice of the community does have the power to affect real change,” Pourch said.

Jacksonville’s urban core has a unique architectural landscape. One that has been shaped by many different hands for over a century.

Historic preservation can serve to advance the education and welfare of residents, creating a place that has depth and character. Protecting and preserving sites, structures or districts which reflect elements of local or national cultural, social, economic, political, archaeological or architectural history has many purposes as well as rewards. Things like strengthening local economies, stabilizing property values, fostering civic beauty and community pride, and last but not least the appreciation of local and national history.

“Some modern development is fine, but to replace valuable historic structures, residential or commercial, with contemporary structures, well, we lose our identity,” real estate agent and UNF alumni, Cindy Corey, said. “These buildings offer a glimpse at our history. They are what make us Jacksonville, the authenticity and character of our city.”

The Doro building is not technically classified as a historic landmark, though not for lack of trying. Reports that were filed in 1989, 1991 and again in 2003 identified that the property potentially met the standards for local historic designation. Obtaining this designation was, evidently, not a priority for the City of Jacksonville.

“There isn’t currently a culture of preservation in the city or the development community,” Delaney said. “And for a long time there wasn’t one in the general public but we are starting to see that change.”

The Doro building was in use up until 2016. It was sold to Rise, a Valdosta-based development firm, in 2019.

Rise is planning to demolish the existing buildings and construct in their place an 8-story, 247-unit mixed-use apartment project featuring retail and structured parking on the property. Much like the Brooklyn 220 and Brooklyn Station projects.

According to their website, Rise Properties describes itself as a developer-owner-operator whose “team of expert underwriters continually reviews markets and investor requirements to deliver the highest-quality investment opportunities for our partners and RISE.”

It is worth noting that the Brooklyn projects have had mixed results. Most visibly, the failures in the Unity Plaza/220 Riverside development project. Regardless of these results, more development will continue.

While demolition has been plentiful in Jacksonville’s urban core, it has been years since there was any new construction. 2014 to be specific, and the new structure was a parking garage. So to be fair, the Rise project could breathe new life into a long stagnant core.

This redevelopment project closely parallels the proposed projects for the old shipyards, where Jacksonville Jaguars owner and venture capitalist, Shad Khan, hopes to construct a 49,000 square-foot convention center and hotel. All of which could be the starting point for two decades of development in Downtown’s Sports and Entertainment District.

This long-term development could actually be good news for those who take the side of preservation. “New project designs need to be inspired by the existing story of the city and the surrounding context and strive to retell that story while adding their own chapter. However, this goal is not easy and requires a developer willing to make a long term investment in the future of our city,” said Pourch.

Jacksonville’s ‘downtown’ spans 3.9 miles across five distinct areas. This has created unique challenges. Developers are hesitant to develop housing because there isn’t enough retail to support it and they are hesitant to build retail because there isn’t the residency to support it. The projects slated for the Sports and Entertainment District could potentially help bridge this gap.

“It can be difficult to incrementally build when you are starting with an empty area,” Pourch said. “Is it sustainable? I don’t know, but we are going to find out and hopefully it’s a yes. But still, preservation is the best way to create spaces within the existing fabric of a city. Why demolish an existing building when there are empty lots all around it?”

__

For more information or news tips, or if you see an error in this story or have any compliments or concerns, contact editor@unfspinnaker.com.