150 armed, masked men took two black men — Bowman Cook and John Morine — from a county jail against their will and without any resistance from law enforcement, on Sept. 8, 1919. The mob took the two men and shot them, and then dragged one of the bodies behind a car several blocks to be left in front of a hotel at Hemming Plaza.

That incident was part of what has become a deep scar on America’s, and Jacksonville’s, history. A new exhibit installed in the Thomas G. Carpenter Library highlights specific instances of Jacksonville’s race-based hate crimes, primarily terror lynchings, for the people of this city to recognize as part of Jacksonville’s past.

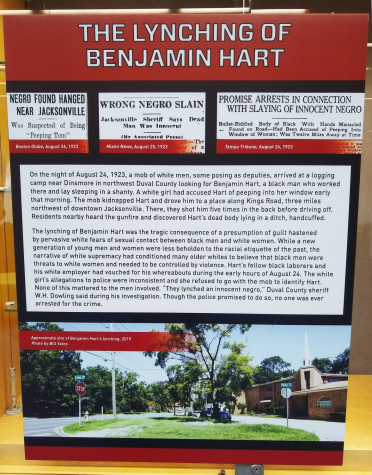

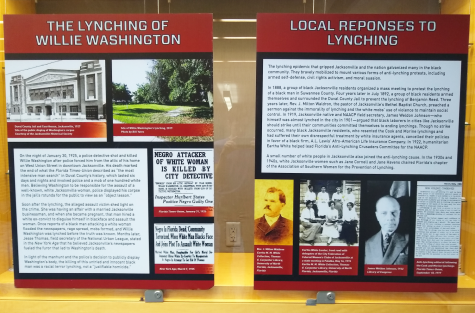

“An Era of Racial Terror: Jacksonville’s Legacy of Lynching” is displayed at the library until Feb. 29, and focuses on the killing of Bowman Cook, John Morine, Willie Washington, Eugene Burnham, Edgar Phillips and an unnamed black man by racist white mobs from 1909 to 1925.

UNF Assistant Professor of History, Dr. Felicia Bevel, expressed the gripping nature of handling the material of the exhibition, upholding the responsibility of an educator with a “lens of resistance” in portraying the history.

“Part of my own intentionality behind researching and teaching on topics of racial violence is to really understand that encountering these histories involves not only intellectual labor, but also emotional labor,” said Dr. Bevel. “It’s not just understanding the content, for instance, of a newspaper article about a lynching. Understanding the tone, understanding the context in which such violence can merge. But it’s also about how we, in the contemporary moment, are processing that information.”

Dr. Bevel’s work with the exhibit and Special Collections involves not just educating viewers, but doing so in a way to respect the victims of these hate crimes. Bevel mentions that the panels of the exhibit do well to call these crimes out for what they are, while still commemorating the lives of those lost.

“The exhibit, quote, ‘honors the memories of those whose lives were taken as a political message in a racial battle for social mastery during the Jim Crow Era’,” said Bevel. “And then as the panel goes on to say, that political message was explicitly legalized white supremacy. And so in focusing on first the memories of lynching victims, the exhibit shifts attention from the performative white supremacy to the victims themselves. And then by explicitly naming it as an act of white supremacy, I think that is also a work of resistance in and of itself.”

Florida saw more than its fair share of racially fueled crimes. Mobs in the Sunshine State lynched more people per capital than any other state, with 0.594 killings per 100,000 people. Florida had the fifth highest total of recorded lynchings with 331. The racial divide in America is still evident today, and these race-based crimes and lynchings were still happening through the south in the 1960s.

The exhibit shows the spaces where lynchings occurred, but in the state they are today as streets and sites that Jacksonville natives drive past or walk by everyday. The panels and photos purposefully don’t show the actual lynchings and crime scenes as an act of resistance and respect to the victims.

“This is one of the most important ways in which this exhibit is doing that resistance work because in that way it’s really mediating the viewers’ encounter,” Said Bevel. “Along with victims body parts, rope, matches, tree limbs and other ‘souvenirs’ from lynching scenes during the late 19th through the early to mid-20th century, we would also have photographs of actual lynchings by amatuer and professional photographers take place.”

These explicit images were part of the propaganda used by the same racist hate groups that enacted the crimes.

“These photographs were in circulation, they were being bought and sold, they emerged on postcards, they were passed to family members to very much celebrate and commemorate these ‘ordinary’ acts of violence,” Bevel said. “These photographs often featured a white mob, sometimes as small as five, sometimes as large as thousands of people, surrounding a man woman or child, about to or having already been lynched.”

The exhibit displays several posters with detailed information concerning these atrocious crimes. In what was arguably the darkest period of American history, Jacksonville was not immune to the negativity, and the exhibit also highlights the city’s response to these instances of hate and violence.

The display can be found in the main lobby of the library, directly to the left of the entrance by the staircase. There are also additional supplemental archives and historical documents in the Special Collections Reading Room presented in conjunction with “An Era of Racial Terror”.

Dr. Scott Matthews, history professor at Florida State College at Jacksonville, and Dr. David Jamison, associate professor of history at Edward Waters College, spearheaded the research for this exhibit and their lecture series “Rooted in Duval: History, Memory & Legacy”. The exhibition is supported by a grant and funding from the Community Foundation for Northeast Florida, Baptist Health, the Florida Humanities Council, and the National Endowment for the Humanities.

—

For more information or news tips, or if you see an error in this story or have any compliments or concerns, contact editor@unfspinnaker.com.

Beverly Bishop | Feb 21, 2020 at 6:09 pm

I have been an employee at FSCJ south campus for the past 10 years. This is the first year I have been disappointed due to no exhibits or references for Black History month in the library or on the campus instead adopting dogs is everywhere. When ask why Black History is not displayed I was told they did not have another table.