WASHINGTON (AP) — The head of an obscure federal agency that is holding up the presidential transition knew well before Election Day that she might soon have a messy situation on her hands.

Before Nov. 3, Emily Murphy, the head of the General Services Administration, held a Zoom call with Dave Barram, the man who was in her shoes 20 years earlier.

The conversation, set up by mutual friends, was a chance for Barram, 77, to tell Murphy a little about his torturous experience with “ascertainment” — the task of determining the expected winner of the presidential election, which launches the official transition process.

Barram led the GSA during the 2000 White House race between Republican George W. Bush and Democrat Al Gore, which was decided by a few hundred votes in Florida after the U.S. Supreme Court weighed in more than a month after Election Day.

“I told her, ‘I’m looking at you and I can tell you want to do the right thing,'” recalled Barram, who declined to reveal any details of what Murphy told him. “I’ll tell you what my mother told me: ‘If you do the right thing, then all you have to do is live with the consequences of it.'”

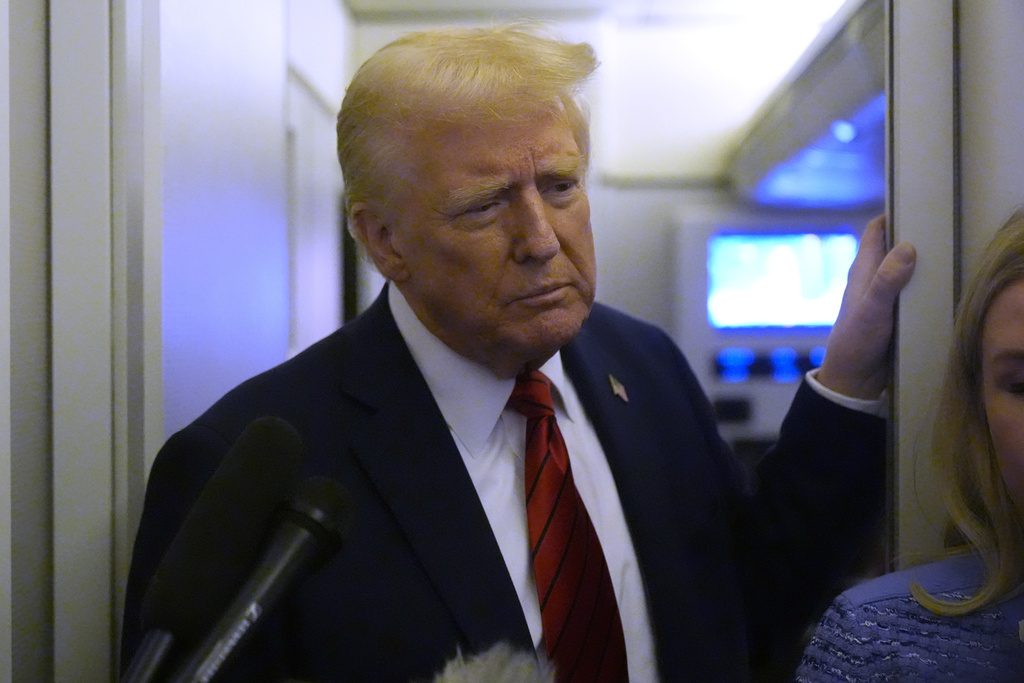

It’s been 10 days since President-elect Joe Biden crossed the 270 electoral vote mark to defeat President Donald Trump and win the presidency. Unlike the 2000 election, when the winner of the election was truly unknown for weeks, this time it is clear that Biden won, although Trump is refusing to concede.

But Murphy has yet to certify Biden as the winner, stalling the launch of the official transition process. When she does ascertain that Biden won, it will free up money for the transition and clear the way for Biden’s team to begin placing transition personnel at federal agencies.

Trump administration officials also say they will not give Biden the classified presidential daily briefing on intelligence matters until the GSA makes the ascertainment official.

Murphy declined to be interviewed for this article. A GSA spokesperson, who refused to be identified by name because of the sensitivity of the matter, confirmed that Murphy and Barram spoke prior to the election about his experience in the close 2000 election.

The White House has not said whether there have been conversations about ascertainment between officials there and at GSA.

On social media and cable, Murphy is being castigated by those on the left who say she is thwarting the democratic transfer of power. Some Trump backers, for their part, say she’s doing right by the Republican president, who has filed a barrage of lawsuits making baseless claims of widespread voter fraud.

Murphy, 47, leads a 12,000-person agency tasked with managing the government’s real estate portfolio and serving as its global supply chain manager. Before last week, she was hardly a household name in politics.

The University of Virginia-trained lawyer and self-described “wonk” had spent most of the last 20 years honing a specialized knowledge of government procurement through a series of jobs as a Republican congressional staffer and in senior roles at the GSA and the Small Business Administration. She did shorter stints in the private sector and volunteered for Trump’s transition team in 2016.

She worked her way up through partisan politics to a position that isn’t in the spotlight, but is undeniably a powerful cog of governance.

“I am not here to garner headlines or make a name for myself,” Murphy said at her Senate confirmation hearing in October 2017. “My goal is to do my part in making the federal government more efficient, effective and responsive to the American people.”

Yet, during her time in government, Murphy has also found controversy.

Murphy took the reins of GSA in late 2017 and soon found herself entangled in a congressional battle over the future of the FBI’s crumbling headquarters in downtown Washington. Trump scrapped a decade-old plan to raze the building and move the agency outside the capital.

Some House Democrats believed that Trump, who operates a hotel on federally leased property nearby, was worried about competition moving into the FBI site should it be torn down and that he nixed the plan out of personal interest. Murphy seemed to give a less than precise answer to a lawmaker who asked about conversations with Trump and his team about the FBI headquarters.

The GSA inspector general found that Murphy in a 2018 congressional hearing gave answers that were “incomplete and may have left the misleading impression that she had no discussions with the President or senior White House officials in the decision-making process about the project.”

In an earlier stint at GSA during the George W. Bush administration, Murphy butted heads with GSA Administrator Lurita Doan.

Murphy, who then held the title of chief acquisitions officer, was one of several political appointees who spoke up in 2007 after a deputy to Karl Rove, then Bush’s chief political adviser, gave a briefing to GSA political appointees in which he identified Democrats in Congress whom the Republican Party hoped to unseat in 2008.

Murphy was among attendees who later told a special counsel that Doan had asked how the GSA could be used “to help our candidates.” Murphy left the agency soon after the episode. Bush forced Doan to resign the following year.

Danielle Brian, executive director of the nonprofit Project on Government Oversight, said the episode had given her hope that Murphy, upon taking over at GSA, would be able to resist pressure from Trump.

“She was essentially a whistleblower,” Brian said. “I really thought she had the potential to stand up to a president. It doesn’t appear to be the case.”

Barram, the Bush-Gore-era GSA administrator, said he felt sympathy for Murphy.

“Republican lawmakers are asking her to be more courageous than they are,” Barram said. “Sure, it’s her decision to make, and she’s going to have to make it one of these days. But they could make it easier if five or 10 of them come out and say: ‘Biden’s won. Let’s congratulate our old Senate colleague.'”