Rush Limbaugh called himself a truth detector, doctor of democracy, lover of mankind, all-around good guy and harmless fuzz ball, titles his legions of followers embraced as he boomed from their radios in a daily ritual.

To those who hated him, the names he conjured were often unfit for print.

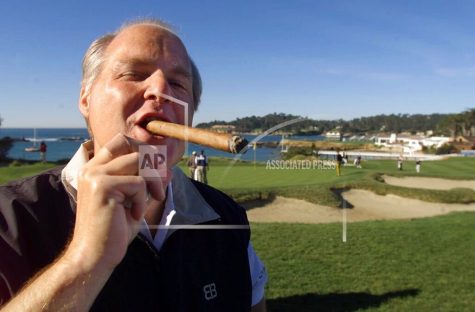

Such was the nature of Limbaugh, who died of lung cancer Wednesday at the age of 70: Prized by adherents as the voice of conservatism, pilloried by critics as the worst of American politics’ extreme right wing.

He was divisive to the very end, but it did little to diminish his importance as the dominant force of talk radio, one of the most influential voices in Republican politics and an architect of the modern right-wing.

Unflinchingly conservative, wildly partisan, bombastically self-promoting and larger than life, Limbaugh had for the past quarter-century galvanized listeners with his politically incorrect, sarcasm-laced commentary. He called himself an entertainer, but with his three-hour weekday radio show broadcast on nearly 600 stations across the U.S., and a massive audience of millions hanging on his every word, Limbaugh’s rants shaped the national political conversation, swaying the opinions of average Republicans and the direction of the party.

He drew people in with his wit, his sense of the theatrical and a made-for-broadcast voice offering listeners a blueprint for what he saw as the grand scheme of the opposition. And he did it with such unyielding confidence, his followers heard his words as sacred truth.

“I want to persuade people with ideas. I don’t walk around thinking about my power,” he told author Zev Chafets in his 2010 book, “Rush Limbaugh: An Army of One.” “But in my heart and soul, I know I have become the intellectual engine of the conservative movement.”

Limbaugh took as a badge of honor the title of “most dangerous man in America,” and called himself “America’s anchorman.” But his assessments of those with whom he disagreed were not nearly so kind.

He called them communists, wackos, feminazis, faggots and radicals. And he would spare none of them.

When the actor Michael J. Fox, suffering from Parkinson’s disease, appeared in a commercial for a Democrat, Limbaugh mocked him and his tremors. When a Washington advocate for the homeless committed suicide, he cracked a string of jokes. As the AIDS epidemic raged in the 1980s, he made the dying a punchline.

To him, 12-year-old Chelsea Clinton was “a dog.”

When the topic was reproductive rights, he didn’t simply voice a pro-life stance, he suggested Democratic ideology in biblical times would have led to the abortion of Jesus Christ. When a woman accused Duke University lacrosse players of rape, she was derided as a “ho,” and when a Georgetown University law student spoke in support of expanded contraceptive coverage, she was dismissed as a “slut.”

When Barack Obama won the presidency in 2008 despite all Limbaugh’s warnings, he didn’t simply voice regret, he said: “I hope he fails.” And with the ugly scenes of a mob insurrection last month at the Capitol still fresh, he was dismissive to calls for an end to violence, comparing the rioters instead to American revolutionaries.

“There’s a lot of people out there calling for the end of violence … who say that any violence or aggression at all is unacceptable regardless of the circumstances,” he said the day after the insurrection. “I am glad Sam Adams … Thomas Paine … the actual tea party guys … the men at Lexington and Concord, didn’t feel that way.”

For all the controversy he embodied, he remained a GOP kingmaker.

His idol, Ronald Reagan, wrote a letter of praise that Limbaugh proudly read on the air in 1992: “You’ve become the number one voice for conservatism.” In 1994, Limbaugh was so widely credited with the first Republican takeover of Congress in 40 years that the GOP made him an honorary member of the new class.

During the 2016 presidential primaries, Limbaugh said he realized early on that Trump would be the nominee, and he likened the candidate’s deep connection with his supporters to his own. Trump, in turn, heaped praise on Limbaugh, and during last year’s State of the Union speech, awarded the broadcaster the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor.

As news of Limbaugh’s death spread, Trump took to Fox News Channel to laud a man he deemed “a legend,” as tributes poured in from across the American right.

“The Super Nova of American conservatism,” heralded Ann Coulter.

Limbaugh inspired the likes of Sean Hannity, Glenn Beck and Bill O’Reilly, and countless lesser-known people who established conservative radio shows in their markets. They followed, too, in pushing the bounds of civil dialogue.

The brand of blunt, no-gray-area debate that Limbaugh popularized spread, from cable television to congressional town hall meetings, from voracious debates over health care to the rallies of the tea party movement.

“What he did was to bring a paranoia and really mean, nasty rhetoric and hyperpartisanship into the mainstream,” said Martin Kaplan, a University of Southern California professor and expert on the intersection of politics and entertainment, who is a frequent Limbaugh critic. “The kind of antagonism and vituperativeness that characterized him instantly became acceptable everywhere.”

Such criticism echoed again and again in his lifetime, but Limbaugh seemed only to push further, assembling an ever-growing list of those branded enemies, of the issues the public was purportedly being fooled on, and the lies the mainstream media was supposedly feeding.

He offered a litany of it all to his listeners, as he did in a 1991 broadcast he heavily quotes in his first book, “The Way Things Ought to Be.” In that single show, in one breathless segment, he railed against the homeless, AIDS patients, criticism of Christopher Columbus, aid to the Soviet Union, condoms in schools, animal rights advocates, multiculturalism, the social safety net and on and on.

Though he often enunciated the Republican platform better and more entertainingly than any party leader, he was an imperfect spokesman. Limbaugh was a portly, cigar-smoking multimillionaire who drew his massive following with his message, not affability.

He came with a checkered personal life that repeatedly put him in headlines. In 2003, Limbaugh admitted an addiction to painkillers and entered rehabilitation. Authorities opened an investigation into alleged “doctor shopping,” saying he received up to 2,000 pills from four doctors over a period of six months, but he ultimately reached a deal with prosecutors that dismissed the single charge.

He was divorced three times, from marriages to Roxy Maxine McNeely in 1977, Michelle Sixta in 1983 and Marta Fitzgerald in 1994. He married his fourth wife, Kathryn Rogers, in a lavish 2010 ceremony. He had no children.

Limbaugh was frequently accused of bigotry and blatant racism through his comments and sketches such as “Barack the Magic Negro,” a song featured on his show that said Obama “makes guilty whites feel good” and that the politician is “Black, but not authentically.” Similar race-fueled comments derailed Limbaugh’s 2009 bid to become one of the owners of the St. Louis Rams.

Through it all, though, his message remained crystal clear.

Key to his monologue was a constant belittling of mainstream media outlets, even as his power grew greater than many of them. He offered a version of the news that was easy to digest, in which his side was truthful and right and all others were liars hell-bent on destroying the country. He strung stories together to portray what amounted to elaborate left-wing conspiracies.

To Limbaugh, his opponents relied on half-truths, bias and outright lies, the very same combination others would say was his magic formula. In his second best-selling book, “See, I Told You So,” he assessed the political debate generated by the mainstream press in a way his critics said was actually Limbaugh’s own modus operandi.

“Lies have become facts,” he wrote. “Lies are facts.”

Rush Hudson Limbaugh III was born Jan. 12, 1951, in Cape Girardeau, Mo., to the former Mildred Armstrong and Rush Limbaugh Jr., who flew fighter planes in World War II and practiced law at home. Rusty, as the younger Limbaugh was known, was chubby and shy, with little interest in school but, from a young age, a passion for broadcasting.

He’d turn down the volume during St. Louis Cardinals games, offering play by play, and gave running commentary during the evening news. By high school, he was already working in radio.

Limbaugh dropped out of Southeast Missouri State University for a string of radio jobs, from his hometown, to McKeesport, Pa., to Pittsburgh and then Kansas City, Mo. He was known as Rusty Sharpe and then Jeff Christie on the air, mostly spinning Top 40 hits and sprinkling in glimpses of his wit and conservatism. But he never gained the following he craved.

He admitted he was often driven by a desire to be liked, even though his pulpit drew hatred as much as love. “One of the early reasons radio interested me was that I thought it would make me popular. I wanted to be noticed and liked,” he wrote.

He gave up on radio for several years beginning in 1979, to take a front-office job with the Kansas City Royals, but ultimately returned to broadcasting, again in Kansas City and then, in Sacramento, Calif.

It was in California, in the early 1980s, where Limbaugh really hit a stride and garnered an audience, broadcasting shows dripping with sarcasm, full of his signature bravado, and railing against liberals. The stage name was gone. Rush Limbaugh was on the air, and the public figure who would become known to millions essentially was born.

Limbaugh began a national broadcast of his show in 1988 from WABC in New York, heard in a smattering of markets around the country. His grandstanding know-it-all commentary quickly gained traction, but Limbaugh was dismayed by his reception in New York. He believed the move meant he’d be welcomed by the likes of Peter Jennings, Tom Brokaw and Dan Rather. He was wrong.

“I came to New York,” he wrote, “and I immediately became a nothing, a zero.”

He had a late-night television show in the 1990s which drew notable ratings but lackluster advertising due to fear of his divisive message. The feelings he could stir were demonstrated when he filled in as host of the “Pat Sajak Show” in 1990, when audience members called him a Nazi and repeatedly shouted, disrupting the broadcast.

Ultimately, Limbaugh moved his radio show to Palm Beach, Florida, where he bought a massive estate. He told The New York Times in 2008 that his eight-year contract with Premiere Radio Networks would bring him an estimated $38 million annually, in addition to a nine-figure signing bonus. As of 2012, Premiere estimated up to 20 million people heard his broadcasts each week. Arbitron, a radio ratings authority, said it couldn’t verify that figure, but there is no question that no one came close to his reach or his influence.

“When Rush wants to talk to America, all he has to do is grab his microphone. He attracts more listeners with just his voice than the rest of us could ever imagine,” Beck wrote in a 2009 article for Time magazine. “He is simply on another level.”

Polls consistently found Limbaugh regarded as the voice of the Republican Party. His followers, whom he dubbed “Ditto-heads,” were unwavering in their enthusiasm, even when he was attacked by opponents or faced personal hurdles of his own.

For all the criticism he received for his message, he was successful in large part for the certainty with which he delivered it, never questioning opinions he regarded as undeniable truth.

“Do you ever wake up in the middle of the night and just think to yourself, ‘I am just full of hot gas?’” he was asked by David Letterman in a 1993 appearance on “The Late Show.”

“I am a servant of humanity,” he replied. “I am in the relentless pursuit of the truth. I actually sit back and think that I’m just so fortunate to have this opportunity to tell people what’s really going on.”