NEW DELHI (AP) — The frenzied fury against Muslims began with provocative songs played by Hindu mobs that called for violence. It ended with Muslim neighborhoods resembling a war zone, with pavements littered with broken glass, charred vehicles and burned mosques.

On April 10, a Hindu festival marking the birth anniversary of Lord Ram turned violent in Madhya Pradesh state’s Khargone city after Hindu mobs brandishing swords and sticks marched past Muslim neighborhoods and mosques. Videos showed hundreds of them dancing and cheering in unison to songs blared from loudspeakers that included calls for violence against Muslims.

Soon groups of Hindus and Muslims began throwing stones at each other, police said. By the time the violence subsided, the Muslims were left disproportionately affected. Their shops and homes were looted and set ablaze. Mosques were desecrated and burned. Overnight, dozens of families were displaced.

“Our lives were destroyed in just one day,” said Hidayatullah Mansuri, a mosque official.

It was the latest in a series of attacks against Muslims in India, where hardline Hindu nationalists have long espoused a rigid anti-Muslim stance and preached violence against them. But increasingly, incendiary songs directed at Muslims have become a precursor to these attacks.

They are part of what is known as “saffron pop,” a reference to the color associated with the Hindu religion and favored by Hindu nationalists. Many such songs openly call for the killing of Muslims and those who do not endorse “Hindutva,” a Hindu nationalist movement that seeks to turn officially secular India into an avowedly Hindu nation.

For some of the millions of Indian Muslims, who make up 14% of the country’s 1.4 billion people, these songs are the clearest example of rising anti-Muslim sentiment across the country. They fear that hate music is yet another tool in the hands of Hindu nationalists to target them.

“These songs make open calls for our murder, and nobody is making them stop,” said Mansuri.

The violence in Khargone left one Muslim dead and the body was found seven days later, senior police officer Anugraha. P said. She said police arrested several people for rioting but did not specify whether anyone who played the provocative songs was among them.

India’s history is pockmarked with bloody communal violence dating back to the British partition of the Indian subcontinent in 1947. But religious polarization has significantly increased under Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Hindu nationalist government, with minority Muslims often targeted for everything from their food and clothing style to inter-religious marriages.

The hate-filled soundtracks have further heightened tensions, but the creators of these songs see them as a form of devotion to their faith and a mere assertion of being a “proud Hindu.”

“India is a Hindu nation and my songs celebrate our religion. What’s wrong with that?” said singer Sandeep Chaturvedi.

Among the many songs played in Khargone before the violence, Chaturvedi’s was the most provocative. That song exhorts Hindus to “rise” so that “those who wear skull caps will bow down to Lord Ram,” referring to Muslims. It goes on to say that when Hindu “blood boils” it will show Muslims their rightful place with their “sword.”

For Chaturvedi, a self-avowed Hindu nationalist, the lyrics are not hate-filled or provocative. They rather signify “the mood of the people.”

“Every Hindu likes my songs. It brings them closer to their religion,” he said.

Chaturvedi’s assessment is partly true. Despite the tacky production quality, poorly matched lip-synching and repetitive techno beats, many of the music videos for these songs have millions of views on YouTube and are a hit among the country’s Hindu youth.

Music in a variety of languages, and often in praise of various Hindu deities, has historically been an important part of Hinduism. Bhajan, a style of devotional music performed in temples and homes, remains a key part of this tradition. But observers say the gradual rise of Hindu nationalism has encouraged a more aggressive form of music that spawns anti-Muslim sentiments.

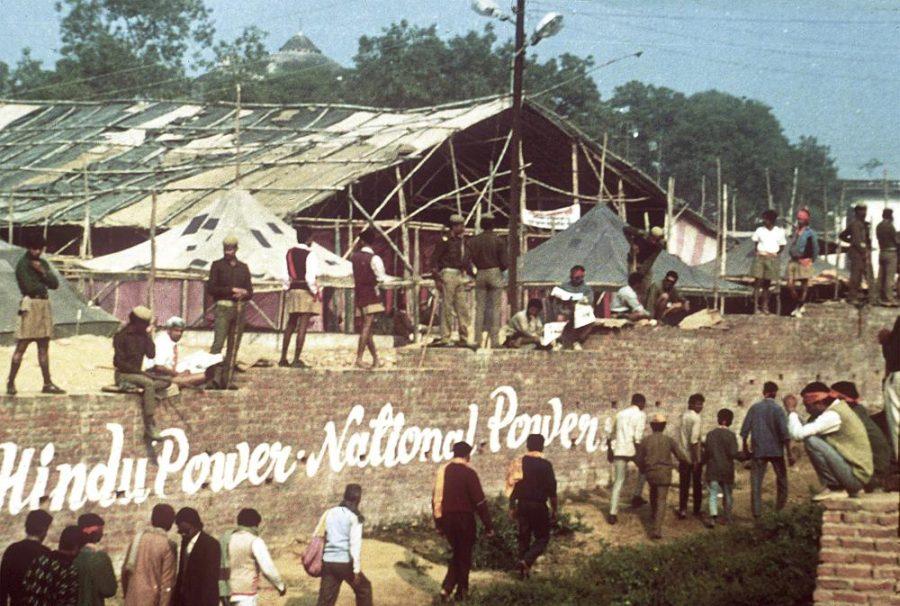

Nilanjan Mukhopadhyay, a journalist based in New Delhi who has written a biography on Modi, said the hate songs were first harnessed in the early 1990s by Hindu nationalists through audio cassettes that were set to the tune of popular Bollywood music, helping them appeal to younger listeners. The beginning of that decade saw a violent campaign by India’s right wing that in 1992 led to the demolition of a 16th-century mosque in central India by a Hindu mob, catapulting Modi’s party to national prominence.

Mukhopadhyay said the songs have since become a “time-tested trope” of Hindu nationalists to “insult Muslims, disparage their religion and provoke them into responding.”

“Most mob attacks against Muslims follow a similar pattern. A large procession of Hindus enters Muslim neighborhoods and plays hate speeches and incendiary songs which inevitably escalates into communal violence. The songs are, in fact, played with even greater vigor in front of the mosques to elicit a response from Muslims,” said Mukhopadhyay, who has also written about major riots in India.

Over the years, the songs have become common during Hindu festivals and are not just limited to the fringe.

The day violence struck Khargone, T. Raja Singh, a lawmaker from Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party, led a similar procession of Hindu devotees in southern Hyderabad city and belted out a self-composed song that made veiled references to the removal of Muslims from the country. Police charged him with “hurting the religious sentiments of people.”

Similar songs that called for Hindus to kill those who do not chant “Jai Shri Ram!” or “Hail Lord Ram,” a slogan that has become a battle cry for Hindu nationalists, were also played in front of mosques in multiple Indian cities on the same day. They were followed by a wave of violence, leaving at least one dead in Gujarat state.

Meanwhile, the demand for these songs keeps rising.

Last week, the singer Laxmi Dubey performed some of her hits before a Hindu gathering in central India’s Bhopal city. In one song, she exhorted a cheering crowd of Hindus to “cut off the tongues of enemies who speak against Lord Ram,” videos from the event showed.

On Saturday, the same song was played in New Delhi during a procession marking another Hindu festival. TV broadcasts showed hundreds of Hindu youth, brandishing swords and homemade handguns, marching through a Muslim neighborhood as loudspeakers blasted the hate-filled music.

In a phone interview, Dubey said it showed her music was widely accepted.

“It is what people want,” she said.

___

Associated Press writer Omer Farooq contributed to this report from Hyderabad.